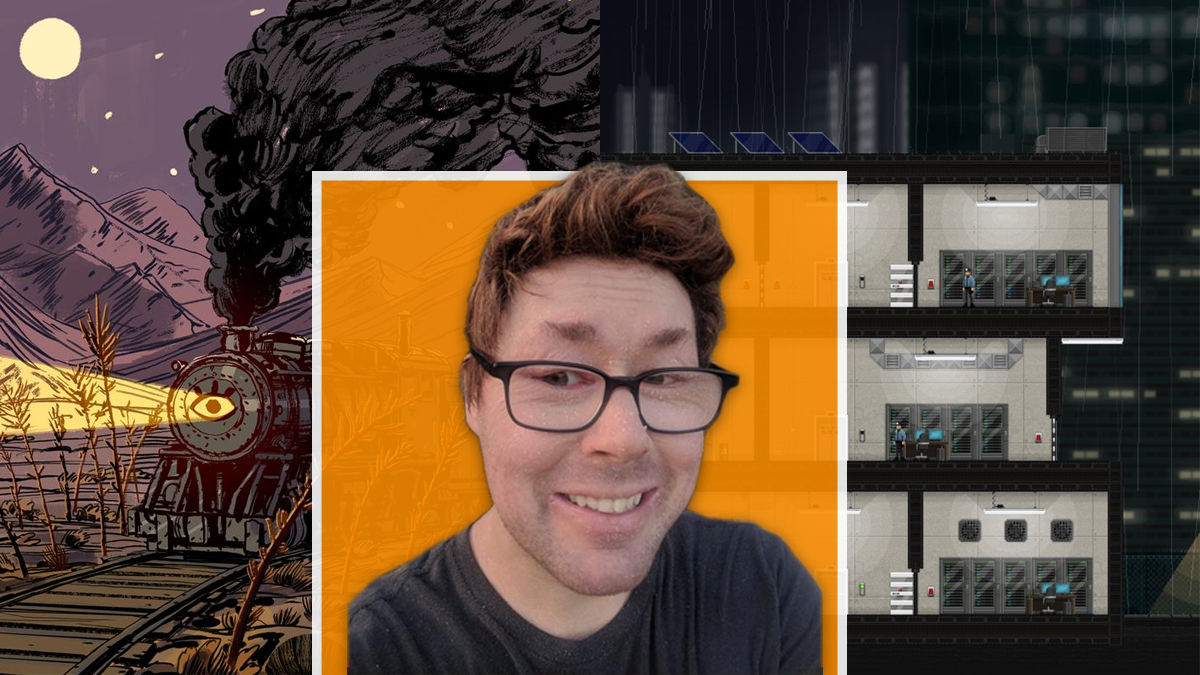

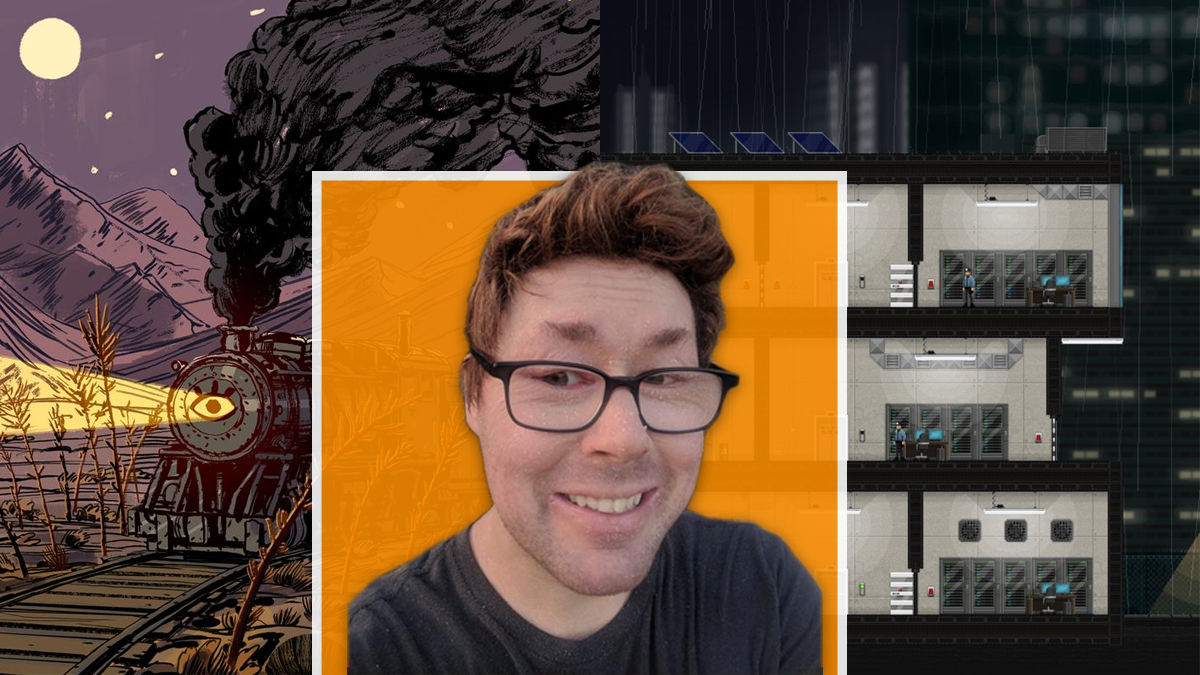

A Persistent Musician Who Wanted to Make Games: Interview with Ryan Ike

The composer for Where The Water Tastes Like Wine and Gunpoint talks about his creative process and how his dreams came true.

Ryan Ike had always dreamed about making music for video games, but when he started networking and looking for his place in the industry, indie gaming was a newborn child and the lack of job offers almost made him reconsider his ambition. But he persisted through motivation, inspiration and a solid goal.

After many rounds of relentless searches, Ike decided to participate in a competition hosted by game developer Tom Francis, who was in the process of making his stealth-based puzzle-platformer Gunpoint. His determination got him the prize of getting his first gig in the industry. From there on he never stopped working and has recently released his highly praised album for the narrative driven, American folk tale Where The Water Tastes Like Wine.

In an interview with The Indie Game Website, Ryan Ike discusses his early steps, his journey through the beginning of indie gaming as an industry and his recent work in Dim Bulb Games’ title.

TIGW: Could you tell me a bit about your origins as a composer and what kind of music have you listened to through the years?

RI: I’m one of those people that always wanted to do something with music since I was a little kid. But when I was a kid that was a very amorphist thing. I’d say like “Yeah I want to be a musician when I grow up”. What does that mean? That’s not anything. Do I want to perform? Do I want to write? Do I want to play in an orchestra? I didn’t know, I just had that loose idea. But I had always engaged with music from the media that I consumed, and especially video game music. Whatever games I was playing, especially Final Fantasy and stuff like that, Nobuo Uematsu was really huge for me because, as a kid, that was the first time I saw music that was really kind of trying to work your emotions in the same way that music from film tries to do. I was really engaged by that. With the Final Fantasy series growing up it was the first experience I had where music in a game had character themes. It was trying to call back to earlier things with music and help to really tell the story with music in a way that I hadn’t really seen in games up to that point. Tons of great music aside, that was the first time that I was like “oh shit, this is telling a story, not just trying to be catchy, which I also love”. I kind of came to actually be a composer really late. I studied music throughout high school and in college. It was right at the end of my college degree, which is just a general music degree, when I was “crap, I want to be writing and making my own music, that’s what I want to do”. I ended up having to go to grad school because I was scared and didn’t want to be out in the real world yet. In indie games you don’t need a masters degree, nobody cares. I learned a little more about how to work with live performers and doing arrangements and that kind of things. When I got out of grad school I hated all the music that my program wanted me to write. It was all this atonal kind of experimental music that I appreciate the value of, but I don’t like. That was the driving thing that made me get out of grad school and say “I have to try doing music for games”. It’s kind of what I always secretly wanted to do. It was either that or being bummed out.

TIGW: How did you get into composing music for video games? Was that something that you thought about doing previously as in a fantasy or actual goal in life?

RI: I always loved music that tells a story, especially when connected to some kind of media. Games were fascinating to me because it was the only place that I could think of where music was interactive. Where it played back and had to adapt to what the listener, in this case the player, is doing. I thought that it was so cool to get to write music for a medium where the music has to change based on what someone else is doing. This was around the time when the indie scene was just starting to pick up, that first wave of indies like Braid and Super Meat Boy. I kind of lucked out because up to that point there was a countable number of jobs for game composers in the AAA industry, and that was it. The indie scene started to blow up and suddenly there’s all these opportunities. My first gig that went anywhere was a game called Gunpoint, and I ended up getting it just because I was networking and trying to meet people in the industry everywhere, but especially on social media. I heard from several other game audio people that Tom Francis, the game developer, was hosting a kind of contest, like an audition. He posted some game footage and said “Hey, write music to this and if I like yours the best, I’ll hire you”. I didn’t know what Gunpoint was, I was just like “Ok, I’m going to try this and it’s just going to be an exercise. I was seeing people like C418 (Note: Daniel Rosenfeld), who wrote the music for Minecraft, and all these other really talented, established game composers were submitting stuff and I was like “I’m never going to get this”. For whatever reason I was one of the people chosen to write music for that. Then I got really lucky on top of it that that project was super successful, that doesn’t usually happen that your first major gig is one that blows up. But this did. It was kind of fumbling around in the dark trying to figure out how to network in the industry, all that stuff, until I just got lucky with Gunpoint and took it from there.

TIGW: You’ve said you’re not a hardcore gamer, but that you certainly play video games. How has your relationship, if any ever existed, with video games evolved through the years? Could you mention a couple of your favourite titles and what are you playing right now?

RI: If a hardcore gamer is someone who plays games everyday, and considers it one of their main hobbies, then yeah, that’s me. I love video games and I have since I was a little kid. I just think I don’t like the word gamer for whatever reason, and no offense to anybody who identifies themselves that way. When I hear that word I think of the negative connotations of that. That’s why I said in another interview “don’t call me that, ugh”. But I definitely play games all the time. The biggest change in my relationship with them is that when I was a teenager and I’d flip over the box and see a bullet point that said “This game has 100 hours of gameplay” and I would be like “Hell yeah!”. Now, as an adult, and like everyone else working in the games industry, I don’t have the time to actually play or finish games, when I see a game coming out and I see through the reviews that “It’s only like 6 hours long”, a lot of people get pissed at that, but I’m like “Hell yeah!”. That is genuinely exciting for me now because I might actually be able to finish that one. I think the last game I finished, which is huge, is Breath of the Wild. But I just finished it and I’ve been playing it almost since it came out. It takes me a long time between work and family. I play whenever I can but it’s little tiny pockets of time. Overwatch is ruining my life (laughs) and taking up almost any time I have to actually play a story based or structured game that has a beginning and end. Overwatch is just like a time toilet were you flush all of your productivity down.

I think one of my favourite games of all time is Katamari Damacy. I love the soundtrack, I love how happy and joyful the whole game is. It’s so stylized that it still looks good. Also Okami, the one based on Japanese ancient folklore where you play as the Sun God in the form of a wolf and it looks like Japanese brush painting. That game does Zelda better than Zelda does it most of the time. I’m currently playing Stardew Valley, Celeste and Into The Breach. All of which are amazing and all of which I suck at. For AAA stuff I just grabbed Bayonetta for the Switch. I loved the first game, and I love that it’s big, dorky and over the top, and that game knows it. It’s really great.

TIGW: How did you get into Where the Water Tastes Like Wine and how was the composing process for its soundtrack? Did you get an early version of the game to work with or did you get access to earlier stages of the thought process?

RI: I met Johnnemann (Note: Nordhagen, creator of the game) when he was going to be at the same PAX that I was at here in Seattle. We chatted a bit and we ended up lining up that project that way. I did get early versions of the game to play and a lot of concept art. It was actually really great, because sometimes you get into a project and a developer will bring you on way too late. Audio people famously get into projects way later than they should be. A lot of developers will say “We’re not ready to talk about audio yet”. But really you should be thinking about audio from the very beginning. The same way you do with the artstyle and the mechanics. Johnnemann did bring me on pretty early in the project, which is great. There was a ton of concept art and folk tales that were written by the artists who wrote the characters, and tales that were not written by the team but already existed and they were using as inspiration. There were early builds of the game I could play, there was a ton of audio references for me. He would send me Youtube videos of music similar to what he wanted. He really helped getting me in the correct state of mind to it. That’s how I prefer to work, being brought on to the project early and watch content and as many ideas as you have about how this game should look and sound and feel. Because that really helps me get to the right place creatively.

TIGW: What influences from your music tastes were involved in Where the Water Tastes Like Wine?

RI: One thing that everybody kind of says is that the main theme Heavy Hands reminds them of Firefly. I always feel like an idiot because I love Firefly and it does sound like that. I think it’s because that’s one of the major touchstones a lot of people have to that kind of western frontier sound that a lot of the game is adjacent to. Stuff like Red Dead Redemption and this kind of modern touchstones for that kind of thing. Those were influences for me. I’ve also always loved that southern folk sound, like a slug guitar and really smooth blues vocals. Getting an opportunity to do that was a really big deal for me.

TIGW: What music aspects did you have in mind when composing for this game?

RI: I wanted to do something really diverse and varied because it’s a game that’s supposed to be about how diverse America is and how different people are, struggling to find the American Dream in different ways. I didn’t want everything to be the same sound, so you have some bluegrass, blues, slug guitar folk, but there’s also a string quartet piece and some Big Ben jazz and music that’s supposed to reflect Navajo culture. One of the ideas I came up with early was “Vagrant Song”, which is a song you here on the world map, the continental United States that your character walks around. As you move through different regions you’ll hear the song appearing with different iterations. In the Southwest it’s going to be more a Mexican inspired track and in Spanish. In the Midwest it’s going to be kind of scandinavian themed and in the South is a folksy-guitared version. I love the idea that as the music travels, and it’s shared with other musicians, it changes and takes a life of its own. It’s a lot of what this game is about.

TIGW: How did you choose the singers that matched your idea of the OST?

RI: I got really lucky with that because one of the singers you hear the most in the soundtrack is a guy called Joshua Du Chene, who’s a friend of mine. One of the great things about working in indie games, especially as an audio person, is that you just meet a ton of awesome singers, musicians and fellow composers. So it’s really great when you suddenly need a lot of live performers and you have a lot where to draw from. I already knew he sounded amazing and he’s on the soundtrack multiple times, he can really change his voice to suit different tracks. He sounds very different on all three tracks that he’s on. He can morph his voice box and be a different person. There were several performers like that in the soundtrack, that I already knew were super gifted. May Claire La Plante, who’s another person that you hear on the main theme, I already knew I wanted to work with her. Others I had never worked with before or didn’t even know already and I just reached out to people who I got recommendations for through social media. I got really lucky than I found these incredibly talented people like Akenya Seymour, who sings on two tracks on the album, she has this amazing smokey quality to her voice, it’s just incredible the range that she can hit. Jillian Aversa who sings on the bluegrass version of “Vagrant Song”, she normally is more of like an aparatic singer, and I asked her to take it into a country direction and she just nailed it. It’s a mixture of people that I knew in my community and from deep dives into the internet to find performers and really lucking out. I never had to ask for a second take.

TIGW: How did the fact that music is almost always present during the game affect your composing process and ideas? Did this intimidate you in any way, thinking that music was going to be on the spotlight the whole time?

RI: It was a little intimidating because most of the games I’ve written for, music is always present in some way, or it’s present most of the times, so that wasn’t so weird. But Johnnemann was very clear that this is a game about stories and the writing takes center stage but also he really wanted to feature the music in a way that I don’t think I had it featured before. He wanted me to be part of that storytelling process and be very pivotal on how this game operates. That was intimidating because it was like I don’t have that safety blanket of just “Well this is just music that needs to be there just to set the tone and the mood”. No, this is part of the main conceit of the game. Once I got into it I super enjoyed it. It was intimidating at first but then it started to feel really cool. I’m writing a song for a character and it’s not just going to be this background thing, it has to embody this character. Then I’m writing music for the overworld map and it has to evoke this different areas and it’s going to be the only thing people are hearing when they’re not engaging with a story.

TIGW: How important do you think music in video games is, relative to gameplay mechanics, storyline, graphic engine, etc?

RI: I think it’s very important, I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t. One of the things a fellow game composer, a friend of mine who I’ll leave anonymous, got into an altercation on Facebook because somebody told her that music in games doesn’t matter. That you could take it out and it would still be a game. And this is true, but that line of thinking and that kind of attitude is such horseshit. I’m very passionate about it. Yes, you could take music out of a product and it would still be a game. You could take the audio part and it would still be a game, it would still have mechanics and choices. But is it as good? No. That’s like saying that if you take the music out of Star Wars, it’s still Star Wars. Yeah, but you’re taking this pivotal deep massive emotional context out of it. And I think that’s what music in games can provide. Weather you’re playing a story driven game like this, or just Super Meat Boy or some mixture. Music helps get players in the right mood and it helps to set the tone. People wouldn’t be doing millions of covers of game music in Youtube if it wasn’t an engaging, important part of making games.

TIGW: Do you recall any video game OST that gave you a lasting impression?

RI: Well, Katamari Damacy i’ve already mentioned, is one of the big ones. It’s probably my favourite soundtrack ever. It was an album full of different firsts. It was the first time I really heard J-Pop, it was the first time I really heard music with vocals at all in a game. It’s got all this stuff that shouldn’t go together but it does and I love that about it. You can do all these crazy things you wouldn’t normally hear in games and you can put them all together and have it all sound like it’s the same album. That was an influence to me for Where The Water Tastes Like Wine because folk is not a genre you hear as often and it’s made up of many different subgenres. Mashing those things together reminded me of Katamari Damacy. Celeste just came out and that soundtrack is incredible. Anything by Danny Baranowsky, he was one of the first indie game composers that I really looked to when that scene started to blow up. He writes in a style that I’m really down with.

TIGW: What effects did you intend to transmit through your work on Where The Water Tastes Like Wine?

RI: That kind of feeling of time and space. That’s kind of what music is supposed to do in a story driven game. When you sit down to talk to a character, you here their theme come in, you know something about that character. Quinn’s theme it’s meant to sound like going off in an adventure. Then Bertha, who is a woman who loses everything, her theme is a solo banjo that’s kind of resolute and maintained melody, but I wanted it to sound like you don’t have much to make music with. Trying to condense what a character or an area of the US is about.

TIGW: Which song do you think reflects the tonality of the game?

RI: I would say “Heavy Hands”, the main theme. It’s weird because it also took the longest to finish because I wrote a shorter version for the opening trailer. It’s the first piece of music anybody heard for this game and then we decided to write a full sized version to go over the credits and the final scene. It took me like a year and a half to finish it. That whole song is about “I don’t think I’m ever going to actually get to that place of prosperity. I’m going to keep looking until I meet my end.” Is that idea that everybody is hunting for this, and most people know they’re unlikely to find it, but I’m going to look anyway and leave my story behind when I go. That’s definitely the main crystallization of the game for me.

TIGW: You’ve uploaded the original scores for free to your Youtube channel. What was the thought process behind that decision?

RI: The soundtrack is for sale on Bandcamp and it is on iTunes and Spotify and Amazon, and all those places. But this is the first time I’ve put an entire soundtrack up on Youtube. Usually I put just a few selections. This time I decided to just throw everything up and it’s likely something I’ll continue to do in the future because I really want people to hear this soundtrack. I’m very proud of it and my musicians. If money is a barrier to you, and we definitely appreciate people who do support us and purchase the album. But if that’s a barrier, I still want you to hear the hard work that went into this. I just believe that if someone wants to support a composer, or an artist of some kind, even if they can get it for free, they’ll do it.

TIGW: What’s your opinion on indie gaming as an industry right now and its growth through the years?

RI: It’s great. It’s very diverse and becoming even more diverse, that’s always good for me. In indie games you can see games from your typical action or platformer, that you get in your AAA world as well. But you’ll also see games about immigration, depression and relationships. AAA games don’t do that or can’t do that. But it’s so cool that in indie games it feels like there’s no limit on what you can make your game about and what the gameplay can be. Two of my favourite indie games are Hyper Light Drifter, which is this action game with a kind of Dark Souls environmental story overlaying it, and Papers Please, which is about trying to manage immigration in this kind of ravaged country. Those are so very different things and I love that indie gaming is a space that contains them both.

TIGW: Would you like to continue working in this industry? Do you have any particular goals in mind or dream jobs?

RI: Hell yeah! This is literally my dream job and even if I’m having a bad day, like a day when I don’t want to be at work, it’s still so stupid that I actually get to do this for a living. I’m not going anywhere. I always wanted to do the type of music that’s in this game and having an excuse to really tell stories with music and this is a game about doing that. I got to work with performers both new ones, who I met for the first time and are incredible; and the one’s I wanted to work with for a long time. This game gave me that platform. Other dream jobs are just anything that’s new. That’s the most exciting thing, when I get to write any style that I haven’t really tackled before. Getting to write a synth wave soundtrack would be awesome. Getting to do something that’s an orchestral kind of asian sound palette would be really cool. Anything new.

TIGW: Are you working on anything right now that you could tell us about?

RI: I’m always excited for the next project. I have a couple of cool ones that I can’t really talk about yet and that I’m already very stoked about. Unfortunately they’re not announced yet. I’ve got multiple projects right now that I will be screaming about on social media the second I can talk about them. I don’t think I can say anything just yet but I will say I’m working on one project in particular that’s about the most opposite thing I could possibly do after Where The Water Tastes Like Wine. I’m excited to take things in a new and different direction.