Hidden Horror: Layers of Fear developer interview

The creation of a new genre, the prolific Polish indie environment, culture export, the niche behind Silent Hills outrage and much more.

The last couple of years have been really special for small indie game developers living in Poland. The success achieved by CD Projekt Red with The Witcher series and the hype built around their upcoming title Cyberpunk 2077 is just the tip of the iceberg. But CD Projekt Red is not a small company by any means.

The last couple of years have been really special for small indie game developers living in Poland. The success achieved by CD Projekt Red with The Witcher series and the hype built around their upcoming title Cyberpunk 2077 is just the tip of the iceberg. But CD Projekt Red is not a small company by any means.

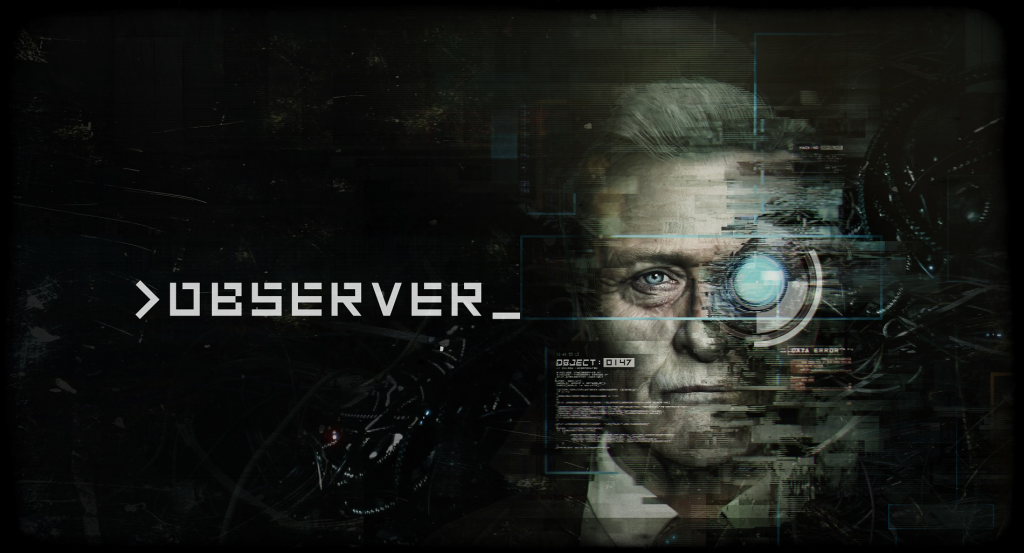

Bloober Team is, although it may not seem that way when looking at the overall results and quality of their products. They’ve been responsible for the greatly praised Layers of Fear and their latest project, Observer, which featured state of the art graphics, quality voice acting (including Blade Runner’s actor Rutger Hauer), sound design and gameplay.

Poland’s metamorphosis and success story will be told in more detail in an upcoming feature, but for the time being, we’ve been able to speak with one of the biggest indie game developing companies in Poland, Bloober Team.

What’s a AAA Indie game? What’s “Hidden Horror” as a genre? How do you export culture through video games? But above all, what makes Poland so special as a video game powerhouse? These topics, and many more, were the subject of an interview that the Brand Manager and Producer from Bloober Team, Rafał Basaj, shared with The Indie Game Website. As always, here’s the uncut, complete conversation.

TIGW: How has Observer performed overall since its release?

RB: I cannot go into too much detail about that. We share our sales and revenue values on a quarterly basis, so I cannot disclose more from that. Although the sales are covered by the publishers and we get reports from them as well.

However, if you think about reception, it was received really well by the market and by the players. People really loved the idea behind the game and it got a lot of really good reviews, including some 10/10 and 9/10. It also received a few awards, most prominently recently we got the Best Indie award from the Emotion awards. Is a very interesting award because it’s not given by the people working only in the video game industry but also by psychologists, sociologists, people who work with people in a daily basis. So they kind of refer to games in a different perspective and is a very important award for us because that’s what we want to do with our games. We want to give the players something to reflect on. That’s the philosophy behind what we do.

However, in terms of sales it wasn’t the biggest launch ever that we had, although with our games that’s how it is. We don’t sell 100,000 copies on day one. The same was with Layers of Fear or every game we had. Games like that are called “Evergreen” titles. They sell on a steady basis throughout the months of their launch, and that’s what we are seeing.

TIGW: Do you agree with the statement that Poland has become a very prolific country in terms of video game development, especially in the indie department?

RB: I would say so. That’s pretty true. I think there’s a variety of reasons behind that. Probably one of the biggest or the two biggest events that explain what’s been happening is that, first and foremost, a lot of companies in Poland use the European Union’s funds to help their development, for R&D or to go to events worldwide. It’s tying with how the government now sees video games in Poland.

At one point the government figured out that we have a lot of talent within the industry and an export value for culture outside the borders of Poland. We also have a film industry, which is what most of the European countries are exporting right now, apart from music. Music is pretty far away from gaming, but movies not so much. In Poland we have extremely indie movies. The niche for these kinds of movies is really small. We get some awards for them, but they don’t have export value in a blockbuster sense. Gaming focuses on entertainment and is a really nice way to export culture and promote Poland outside of our borders. I think that the government figured that out after the success of the first Witcher game.

Moving through the second game, and what CD Projekt Red was able to create around the project, made people from the government look into it, but also what Techland did with Dying Light and, previously, with Dead Island. Those were huge global titles. Young people are also working inside governments around the world and they either play games at some point or they’re familiarized with those concepts. Those two pushes from the governments made people realize that they can make video games in Poland.

The market for creating games in Poland was pretty good recently because the Polish Zloty, the currency, is a rather weak currency in comparison to the American Dollars or the Euro, but if you make games in Poland you earn in Euros or Dollars. The cost of having a company doing video games was pretty low, and it changed with the years that have passed and the experience gained by the people that went into that industry. Those people, you need to keep them in Poland, you don’t want them to go to Western Europe to work on video games. That’s why the costs have grown. We have an established industry right now, but I think that less and less new indie studios will pop up in Poland because it’s getting pretty expensive. Although, if you’re three people working from a basement, that’s fine. Costs are getting higher for companies because of the experience they have to pay for.

The industry is pretty young in Poland right now, that’s the last crucial element. When we moved into the 21st century, after 1997 and the Third Republic of Poland, going back to being a free country, we were building our industries from back then, but the video game industry probably landed to a bigger screen in the 21st century. Poland for a long time had an established image in Europe that we have a great talent. When it comes to video graphics, everyone working in IT, we’re considered a valuable asset. A lot of those people that actually had the knowledge went to work in Western countries when they gained even more knowledge. At one point those people started coming back to Poland, opening their own companies, joining the teams that had been formed back then. Bloober Team is actually born in 2008, almost 10 years old, but we went into the global market with the release of Layers of Fear, which was between 2015 and 2016. During that previous time we were working in smaller projects to gain experience.

Right now the industry looks like we have a lot of talent, and a lot of the young people wanting to get into the video game industry actually have people that will teach them how to do a lot of stuff. If you’re a small company you can develop in Unreal or Unity, there are so many ways for people who want to start in the video game industry and it’s so much easier than before. It’s growing in Poland still, there are more companies opening, people going from big companies to form their own indie companies, a trend that we see globally. We all went through those trends in a short period of time. Ten to fifteen years probably. Something like western countries, even the US or Germany and France, that have been developing games for a lot of time now, stretched for longer periods of time. We had it all compacted in a short period.

People are very passionate about this in Poland, there’s a lot of talent, a lot of ideas. People who come from nowhere, in their late 30s, but they had so many ideas and couldn’t realize them before because there was no industry. Definitely Poland is still a place to develop games. A lot of talent and still cheaper than in Germany, for instance. We need to stay competitive.

TIGW: Could you expand on the involvement of public entities in the video game developing industry for indie games? Were there encounters or dialogue instances during which you agreed on a path to follow?

RB: Definitely the government has reached out to a few companies. The biggest ones at first, like CD Projekt Red. If you think from the development perspective, you’re constantly seeking money and investments. A lot of companies went into the stock exchange market and that’s a place where you start talking not only to people who invest in projects, but also it’s a moment when government entities see you. But when it comes to the path of how it all went down, I think it was a process.

It started with the European Union funds. It’s how I tried to imagine how it worked. I wasn’t at the very beginning. But I think a lot of companies who wanted to create video games in Poland started receiving money from the European Union for the R&D, creating projects. Obviously they had to bring something to the market, because if they wouldn’t, they would have to give the money back. At that point, the government also started to look for smaller projects or indie titles because we had a few of those.

Most of the games built in Poland were considered indie at some point, apart from probably Techland and CD Interactive. That movement that started from the developers who actually gained investment money got the attention of the government as a growing business. There were successful stories in the market that proved we could do things at a global scale.

I still think that one of the most important aspects to this is also- as I said – is sharing the culture of Poland. Basically that’s something that the European Union was looking for as well: that the national identity of the parts of the European Union to be highlighted. The projects that actually gained the funds had to prove that they are promoting the region or the country they came from. A lot of people outside of Poland knew that specific titles were Polish, because people were kind of obliged to tell that it was a Polish game.

TIGW: What role do you think Bloober Team occupies today in the Polish map of indie gaming?

RB: We definitely grew. Right now we’re kind of what a lot of people refer to as “AAA Indies”. What we started with Layers of Fear and then went on with Observer is bringing AAA quality to an indie game. That’s what we wanted to do from the get go: a lot of attention to detail and to making games as a whole experience, to people to feel that it’s not indie or a game made by five people in a small office somewhere in the world. Right now I think we’re one of the five biggest developers in Poland peoplewise, and probably one of the most experienced studios. We’re definitely at the top of the food chain when it comes to the size of the company. Although, because we grew so exponentially, we tend to work in smaller teams and on a few projects simultaneously.

Our games are still indie. The core team for a project probably has around 10 to 20 people. We have a pool of outsource resources that we use, that helps out on each of the projects. We stay close to the indie scene because we like to develop games in that way. It gives us freedom in what we want to do. We don’t want to follow the footsteps of others, like trends made by big US companies, for instance.

We want to cave our own path, that’s one of the reasons we went with the psychological horror genre. We knew there was a niche for that. So it aims to people not necessarily wanting to play a survival horror game, based on dexterity and action. It was a risky move. We knew that the audience was there. Because we’re focusing on one genre and delivering with each new game something new to it, we are learning from past experiences, thinking about how to move the genre forward. It lets us be one of the most recognizable companies from Poland. We’re not in the level of CD Projekt Red, but definitely because we’re sticking to what we’ve envisioned for the company, helps us establish our identity.

TIGW: What you said reminded me of the cancellation of Silent Hills and the removal of P.T. by Konami. The amount of hype the teaser had created for a game in that specific genre was huge. Did that make you feel that sticking to psychological horror had been a good call?

RB: We had envisioned this before the cancellation of Silent Hills and before P.T. was taken out of the servers. The moment it happened it was kind of a realization for us that yes, that’s the path we want to take. There’s all these people out there that actually have spoken very loudly about how they feel on the cancellation of Silent Hills. That was a very crucial moment for us because the community and the players proved to us that what we wanted to do had an audience. There are places in the world where they like it more than in others, like Latin America.

If you look at the culture as a whole, horror has always had a place in it, it’s niche. Whether it was a big or a small niche, it was always there. We knew we had that target audience. If you look at the film industry, you have a wide variety of genres and subgenres to choose from: you have slashers, gore movies, body horror and psychological horror movies. Whatever suited your taste, there was someone creating those movies.

When you look at the video game industry, you didn’t have that. You had survival horror games. At one point we checked the Wikipedia page for horror games, there’s not a single game that’s classified as pure “horror”. It’s non existent. What’s even more interesting, if you go to some events as a developer and you fill out the form of what your company does, if horror is amongst those it will always be labeled as survival. That kind of made us think that we wanted to do other types of games, we didn’t want to do survival games because there are enough of them on the market.

We love horror and watch, read and play any kind of it. There’s a lot of fanatics here. If you want to play them, you have a very small niche of games that try to do something differently. People enjoy psychological horror movies, so why wouldn’t they enjoy games in that manner? We built a whole subgenre behind those ideas that we had and we call it the “Hidden Horror”.

TIGW: Can you expand on the concept of “Hidden Horror”?

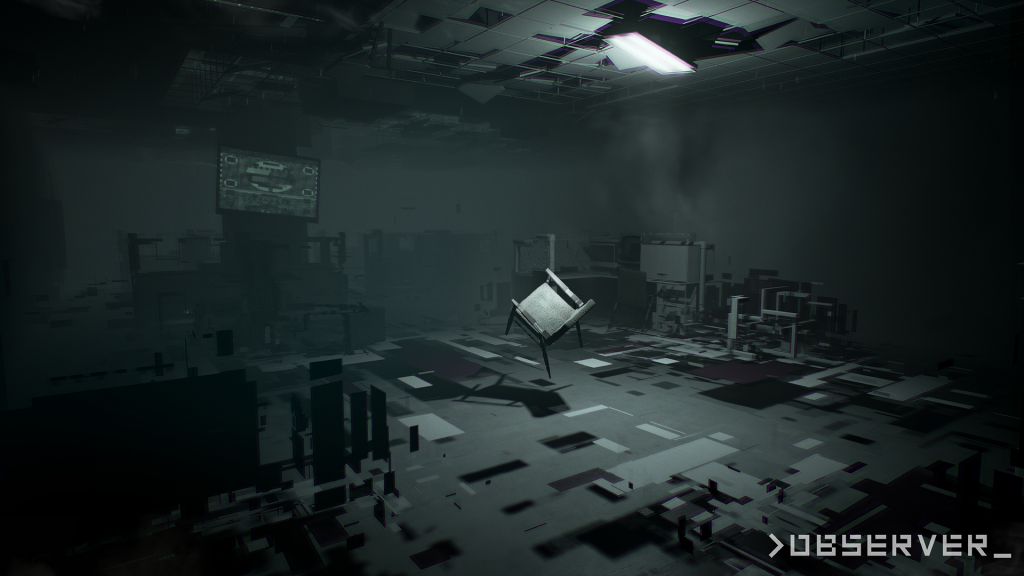

RB: It has only two principles. It expands from the psychological horror genre, but all of the games need to have a subject, most probably from a sociological or psychological branch. The subject for Layers of Fear was the struggle between having a successful family life versus having a successful career. That was the bottom layer for it. With Observer it was the boundaries of humanity that we have explored in many ways through the tenants you can meet through the game and their stories.

It’s something that we’ll be doing with every other game that we have. We want to tell something through our games that has not only the entertainment value, we don’t want to scold or tell people about how they should behave, or what’s wrong and what’s right. We don’t take a stance in that. We give moral dilemmas to the players, which leads us to the second feature of Hidden Horror, which is something that we call “Catharsis 2.0”.

What we want to do is not only for players to relive their tensions and fears like the realization that you’re not afraid anymore of something because you’ve lived through that. Also we want people to stop for a second, either when they’re playing or when they’ve stopped, to ponder what the game was really about. Why did the protagonist do what he did, or why did I choose to do that if I could do something else. We want them to reflect on their own lives, depending on what they’ve seen through the games.

The feedback that we’ve been given after Layers of Fear tells us this actually works. A lot of people come back to us with stories about how our game resonated in their personal lives. Even to an extent that at one point a woman wrote to us that she understood, after playing Layers of Fear, why her husband had left her ten years ago. She realized what went wrong with their relationship, why it had crumbled. She was so immersed in the game, she stopped and actually thought about her own life and how it all pieces together. Maybe we don’t have dozens of these types of feedback, but they’re there.

TIGW: You’ve mentioned CD Projekt Red, and it’s clearly a titan in Poland and in the world. What kind of role does it have in the Polish micro-environment?

RB: Right now there’s success in what other people thought it was impossible to establish a company. A lot of people look up to what CD Projekt Red did. They kind of crave the same success that they had. I wouldn’t say they are a huge role model. I think they’re more a benchmark for other companies. We love the people from CD Projekt Red, they’re extremely talented and they definitely know what they’re doing and how they want to achieve it. A lot of people are analyzing what they did but not copying it. They’re looking for the good values that they brought to the market and trying to do something of their own, because one thing is for sure if you want to be successful: you can’t go after someone else’s footsteps. You have to have something of your own.

TIGW: Does CD Projekt Red have any kind of dialogue with the smaller Polish developers to help them find their own path?

RB: I think that in some extent that’s something that a lot of companies do in Poland. We’re kind of a very tightly knit community. People from CD Projekt Red know people from our company and we know people from Techland and so on. Obviously we share experiences and ideas whenever we can. There’s not so many of us. We learn from each other. To be honest, I think that CD Projekt Red, if they can, tries to share their experiences and knowledge through various events in Poland, but I don’t think that there’s a bigger extent in that matter to what other companies do as well. Recently 11 Bit Studios started publishing smaller games, for instance, helping smaller indies get out there. CD Projekt Red doesn’t do that, although because they’re only a part of the CDP company that owns GOG actually, from that angle they have been helping a lot and they’ve been working with a lot of smaller companies in Poland, but also from the Western or Eastern countries. The industry grew in Poland so much that everyone that has something of value to share, shares it.

TIGW: What kind of influences of Poland’s history and culture did you have for the creation of Layers of Fear, Observer and your upcoming new title, Medium?

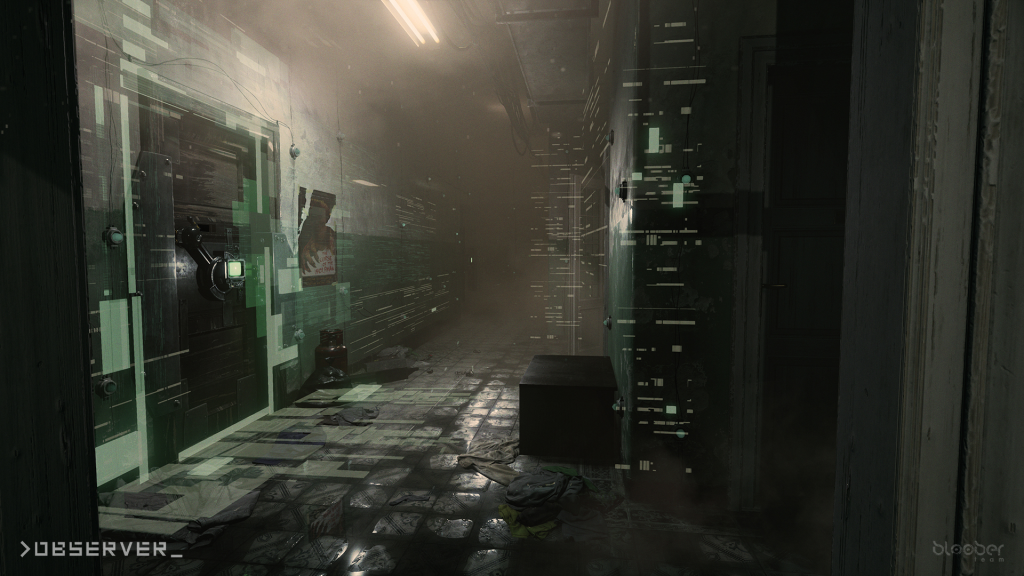

RB: The most prominent example would be Observer. First, the game is set in Krakow, Poland. We’re not afraid to tell people about that. The main building in the game is mapped out from a real building in which one of our employees actually lives in. It has been standing in Krakow for such a long time so we mapped it with a lot of photos, videos. What we always wanted to do was to use a lot of props that we have in our culture, that will not be understandable by people from the Western audiences or the US. Even the car where our protagonist is at the very beginning of the game was done in a way to resemble one of the most cult classic cars from the early 90’s in Poland. The janitor robot cleaner that’s going through the building has a vacuum cleaner on one of its arms and it’s a cult classic in Polish culture as well. If you’d go into the early 90’s any Polish household would have the same one.

We had a lot of these easter eggs for people from this part of the world who would instantly understand the references, but for the rest of the world it was the design, something different, something that they thought to be exotic because it came directly from what we know of our culture, our childhood. There are historical references: the Chiron corporation, which is the evil cyberpunk corp in the game, kind of makes its propaganda kind of like Soviet Russia did in the countries here. There’re a lot of references, even to Polish movies. Scenes developed to resemble the ones from Polish classics. What we wanted to do was to give a lot to the Polish and Eastern communities who would understand them, but also because of that, we made something very exotic to the people from the Western countries. That’s what we like to do. Medium will also be a game that will be happening in Poland.

TIGW: Can you tell us anything about Medium?

RB: It’s still hush-hush. We hope to disclose some information about the game soon, however that’s not something I can discuss at the moment.

TIGW: What do you think makes a Polish storyteller special or unique amongst their peers from around the world?

RB: That’s a tricky question because a lot of people in Poland were raised with the American culture from its TV shows, movies and such. I wouldn’t say we’re special in that way. We just come from a different part of the world, which gives us a different world view on certain subjects. It’s not that we have an established way of telling stories that no one else in the world has. I think that the experiences we had from this part of the world give us that different angle on the stories we tell. Sometimes the plots will be a little bit different because they feel more personal, which is different if you grew up in a patriotic America, the US of A. Poland has the catholic religion as something by which we are recognized in the world. There’s a whole lot of problematics in that sense: how people react to that in Poland, how they see the world through that lens. Everyone has a different environment in which they grew up.

TIGW: There’s a big difference between, for instance, American cult classic books and slavic cult classic books in the way of narrating and looking at life. If you read Hemingway and Dostoevsky, you’ll find an ocean of difference in what they focus on. American classics can be more action based or featuring practical characters, while slavic classics have characters that riddle inside their minds looking for answers.

RB: If you look it that way, that’s probably true. Probably less than in times of those writers, because of the globalization that the whole world went through. But yes, I would say that the dark tones of the stories we tell in Poland is that unique feature. If you look at This War of Mine, it’s a dark story about surviving from the angle of a regular person through the war. If you look at The Astronauts and The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, it’s still a dark story about finding a missing body. We like to tell dramatic stories. We like complex narratives with twists, that are not easy to go through because they have different layers and substories.

We were between Germany and Russia through the war, huge military powers that have been struggling for power for centuries. We were always in the middle. The tragedy theme is out there, definitely.