The 7 Best Minimalist Indie Games

Because realism is overrated.

One of the most defining features of indie games is the freedom with which they can approach their subjects. Without the constraints of large financial risk or audience expectations, indie studios are free to create experiences that sit outside the realm of the norm. Stories and experiences are told in new and unconventional ways, often pushing the medium to its artistic limits. When a game breaks through these artistic limits, it’s often because of the creative freedom afforded to its developers.

Meanwhile, the scarce budgets, lack of manpower, and restricted access to high-end development tools often yield something decidedly abstract. Minimalist indie games often push the concepts of what can be portrayed through a cluster of pixels to the extreme, and often with highly nuanced yet increasingly powerful results. Here, we’re celebrating seven of the best minimalist indie games that used this abstract approach to art direction and gameplay to create profound experiences with fewer on-screen objects than a loading screen.

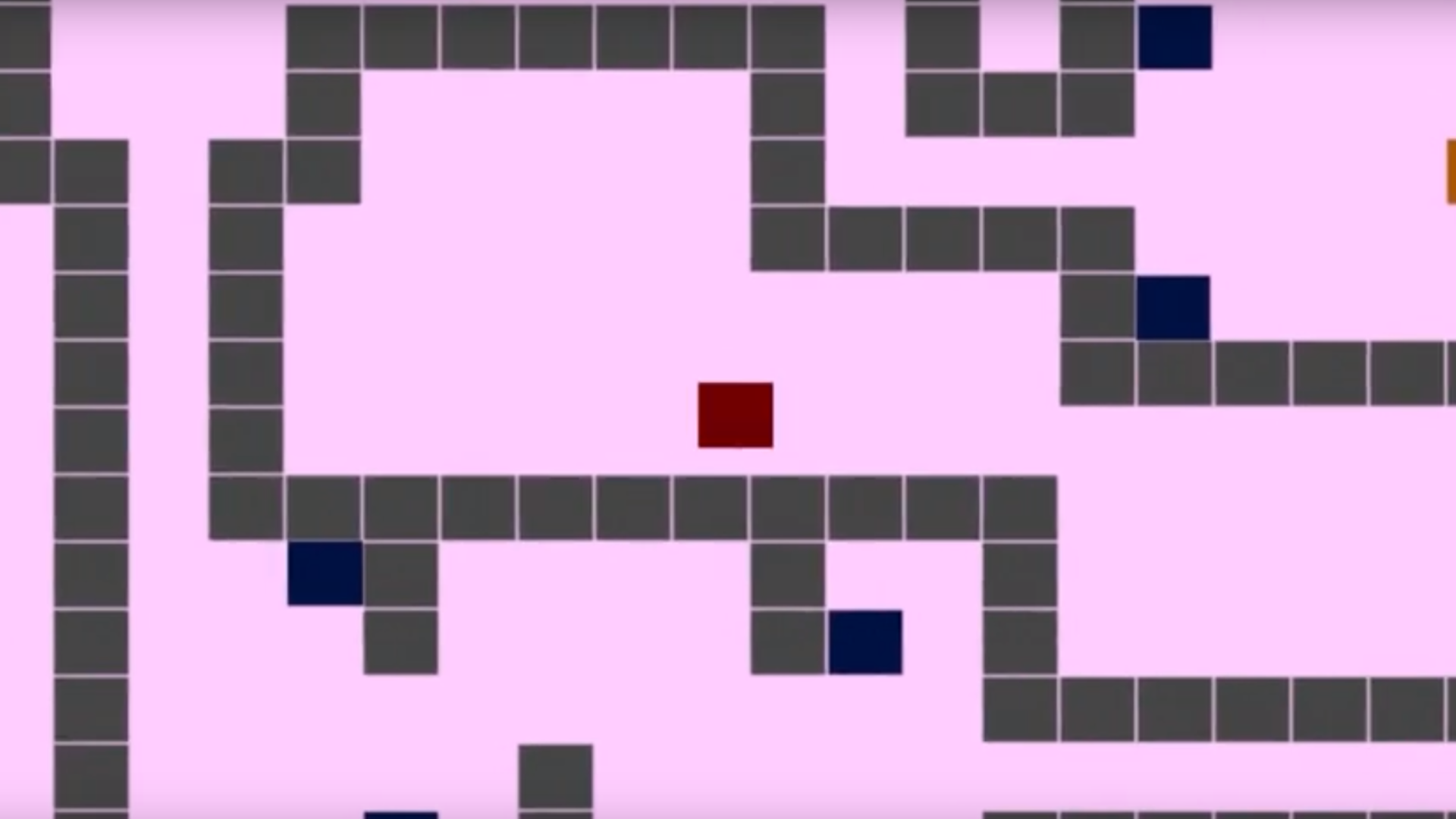

Lim

Lim is the very definition of abstraction born from creative freedom. Created by Merritt Kopas for the Games For Change organisation, the experiences places players in the centre of an identity crisis told entirely through small rectangles. Move your block through the corridors of other differently coloured blocks in an attempt to manoeuvre the puzzle without being forced off the map. Get too close to another colour, and it will begin vibrating erratically, doing everything in its power to aggressively remove you from the space.

Lim starts out as a fun puzzler but quickly becomes a deeply sophisticated ludic narrative exploring the complexities of ‘fitting in’ and the struggle of an identity defined in relation to those around you. A blending mechanic offers the player the ability to change the colour of their block to mix in with other surrounding blocks, a method of survival in the moment but a devastating cost once the threat has passed. It’s this nuanced approach to the messaging behind the game that presents Lim with a unique position of representation, and one that will continue to resonate.

That Dragon, Cancer

That Dragon, Cancer is one of the most heartbreaking games on the indie scene. This is a personal tale of a father honouring his son after his early passing and one that uses abstract and minimalist art and mechanical design to evoke highly potent organic emotions within the player. The narrative takes place over the final months of young Joel’s life as his parents and siblings come to terms with his illness and make sense of the world around them during this awful time. The jagged, fragmented art style and often surreal passages of gameplay are all telling of the scattered fear of the developer telling this story. Meanwhile colour and music work alongside poignantly simple player actions to portray the father’s state of mind.

Speak to anyone who has completed That Dragon, Cancer and you will be met with a heartfelt sigh. The game is emotionally draining, particularly because the minimalist world and character design, combined with an almost stream of consciousness approach to the actual events and player actions, forces you to place your own contextual information into the game. The raw emotional signifiers are left in the game world for you to pick up and organically generate as your own. Using such minimalism to allow the player to create their own contexts and emotional responses is incredibly powerful throughout the That Dragon, Cancer experience.

Thomas Was Alone

Mike Bithell’s seminal and now renowned indie game, Thomas Was Alone is the very embodiment of minimalism in many ways. Bithell had originally created it as a flash browser game and later went on to expand it into the full version that we now all know and love. In the game, players control simple, coloured rectangle shapes each with its own defined personality. These minimalist shapes represent rogue artificial intelligence entities looking to escape the system they’ve found themselves trapped in. Guided by the narration of Thomas, voiced by Danny Wallace, you explore and find your way through the mainframe solving the environmental puzzles it presents.

Thomas Was Alone, like so many of its contemporaries, found inspiration from the world of art. Bithell liked the idea of modernism and minimalism exemplified by the Bauhaus school of thought and fused that influence into the game’s design. This simplistic fusion of thoughtful narration coupled with the game’s abstract design earned it a slew of awards and praise from critics. Bithell has since gone on to cement his name in the industry thanks to his first game’s ability to tell a deep and meaningful story about friendship using only simple rectangle shapes.

Polygod

Polygod combines both minimalistic visuals and randomly generated levels, enemy placement and power-ups, in a single or multiplayer first-person shooter. The inspiration behind the artwork in Polygod comes from Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, perhaps best known for his surrealist cityscapes. The backdrops in the game are often shaded in colours usually reserved only for highlighter pens and the bright, vivid colours wonderfully combine with the flat textures and minimal polygons to create a unique art style.

With all good roguelikes, depth of randomisation is crucial, and it’s in abundance in Polygod. With the blessing system, each level contains several Altars of Worship, offering you powerups in the form of gun customisations which can be mixed and matched with one another to create unique and often bizarre results, such as shooting bubbles, which can be more dangerous than it sounds. Again, with most roguelikes, Polygod has a brutal difficulty curve. The game is undoubtedly a Quake spawn in gameplay and offers both co-op and PvP multiplayer. With such a mixture of minimalist visuals and randomised, different-every-time playstyle, Polygod offers a unique and enticing experience.

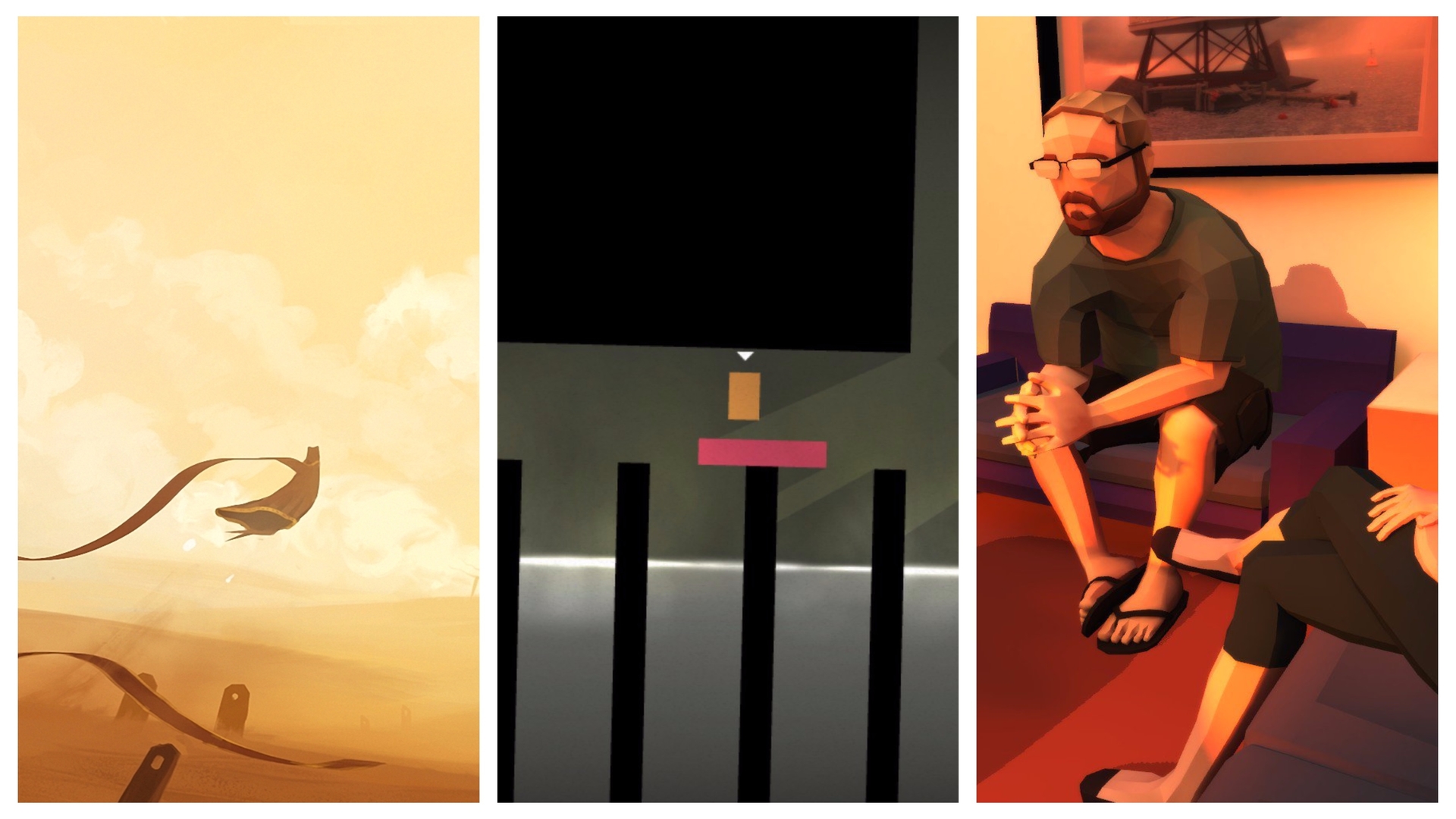

Journey

Journey is a beautiful game. Rolling sandscapes, bathed in light, form the majority of the scenery in the game, speckled with ancient relics of mysterious origin. There are no vivid colours here, instead, a captivating world detailed to the smallest minutiae awaits explorers with open arms, sand gathering on you as you carve a path through the rolling dunes. Characters are enshrouded in cloth, which must be communicated with in order to progress. The main aim of the game is to reach the mountaintop, but it’s just as satisfying to stop and take in the surroundings.

The playtime of Journey is relatively short, but where it shines is in its co-operative mode. You may, while exploring the world, stumble upon another player. It’s up to you whether to work together or explore on your own terms. It’s also entirely possible to play through the game alongside one another without speaking a word to each other. A strange, rhythmic language can be expressed and serves to add to the surreal experience. It’s hard to justify Journey as just a game. It’s an emotional, unforgettable experience that is a true work of art above all else.

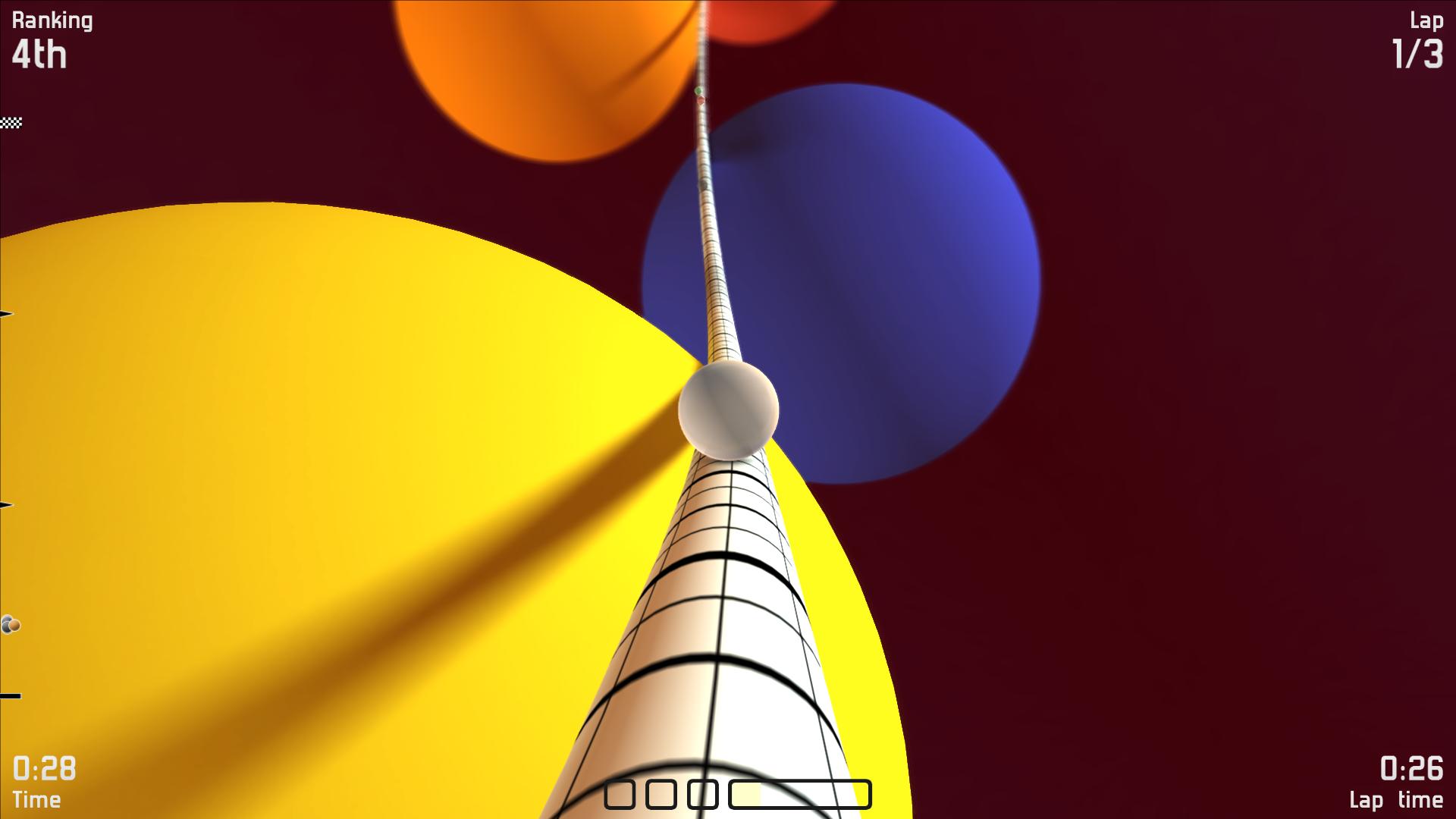

Proun

Taking its name and aesthetic form factor from El Lissitzky’s Proun, a collection of geometric, abstract paintings, Proun takes players through a colourful world of geometric shapes. Moving a ball from one end of a rail to another while also manoeuvring the abstract objects in your way proves to be quite the challenge, and many refer to Proun singularly in terms of its difficulty.

Proun feels like a psychedelic journey through one of Lissitzky’s paintings, easing the player into the minimalist intentions behind the title. However, it’s in this difficulty that Proun’s minimalism really shines. Each level is so blindingly fast that to have any chance of completing it, one must simply memorise the swipes and moves necessary. It’s not only a backdrop of abstract art driving the minimalist nature of this game, then, it’s also the mechanics at play themselves. The process of gameplay has itself been abstracted and reduced to a series of thumb swipes necessary to move onto a different screen.

SUPERHOT

SUPERHOT was a game built around one simple mechanic – time moves only when you move. It’s not just SUPERHOT’s gameplay that is minimal though, the game’s whole design embraces minimalism as a form of expression with the majority of the environments and objects present broken into two opposing colours. The enemies are an angry block red devoid of any defining features with stark black weapons of violence held ready to inflict damage. The white walls and halls burst to life with these bright red manikins only for them to be frozen in time as you stop moving to present what could easily be mistaken for some avant-garde modern art display.

SUPERHOT was a game built around one simple mechanic – time moves only when you move. It’s not just SUPERHOT’s gameplay that is minimal though, the game’s whole design embraces minimalism as a form of expression with the majority of the environments and objects present broken into two opposing colours. The enemies are an angry block red devoid of any defining features with stark black weapons of violence held ready to inflict damage. The white walls and halls burst to life with these bright red manikins only for them to be frozen in time as you stop moving to present what could easily be mistaken for some avant-garde modern art display.

Again, similar to some of the other titles presented here, SUPERHOT still manages to convey a sense of narrative and depth to the player despite its simplistic approach to game design. The player interacts with a computer system – attempting to break its firewalls and access the illicit games inside. Stumbling upon SUPERHOT in this fourth wall breaking manner gives the game a sense of realism and immersion beyond its minimalist representations of action. SUPERHOT is a testament to the fact that you don’t need grade-A, realistic visuals or extremely complex narrative to draw a player in – you just need a core design and approach that’s thought-provoking and engaging for the player.

All of these minimalist indie games have something in common: they all use representations and the resulting organic emotional responses to evoke a powerful response in the user. Whether this is to encourage laser-tight focus as in the case of Proun, or an often devastating emotional connection to characters and situations as in That Dragon, Cancer, each game on this list has pushed the pixel to its limit.

Disclosure: The Indie Game Website’s publisher, Lewis Denby, was responsible for PR for Thomas Was Alone on its original release in 2012. He hasn’t worked with Mike Bithell since, and this had no bearing on its inclusion in this article.