Petscop: The Video Game That Never Existed

How gaming’s greatest creepypasta inspired an unprecedented indie collaboration.

What happens when you blur ‘found footage’ aesthetics with a Let’s Play? Can you truly call a game “lost” if it never existed? Why do communities form around these oblique, creepypasta-inspired oddities?

Petscop, a ‘lost game’ of viral YouTube fame, posits all these questions without really answering them. Much of the game sort of lingers, perched on the edge of something sinister. Its story and underlying lore are deeply embedded in real-life events, but the indirect presentation and commitment to implicit horror allows the game to stay in a viewer’s mind, almost automatically.

The ‘found footage’ genre exploded into mainstream consciousness through the medium of cinema with 1999’s Blair Witch Project, a film that borrowed heavily from the genre’s origins in Cannibal Holocaust to create a piece supported by one singular tension: the question as to whether the film itself was fiction or reality. It wasn’t until 2009 that the Slenderman-inspired Marble Hornets brought the genre to the expanse of YouTube, exploding at the fingertips of viral video surfers and the forums of fan-theorists everywhere.

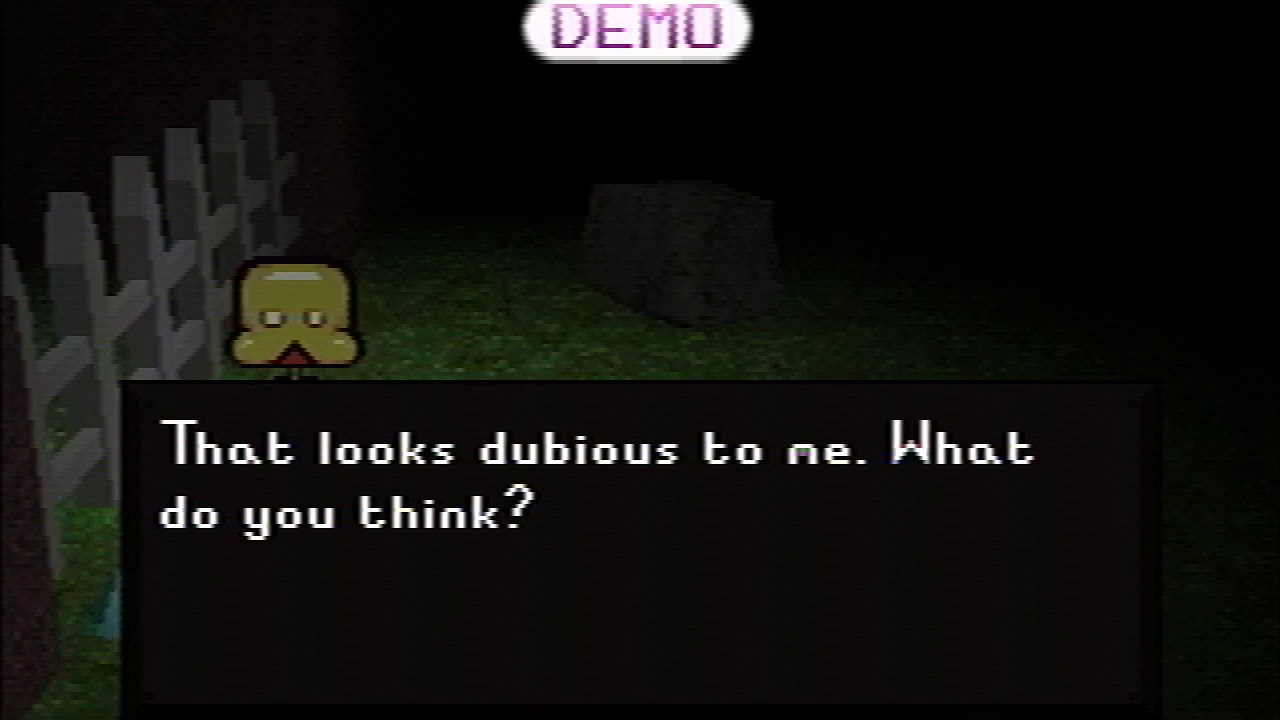

Petscop’s origins channel both film’s reliance on faux-amateurish production and uncanny subject matter through the medium of a Let’s Play formula. On the surface, the premise sounds simple: capture an array of cutesy pets through a distinctly PlayStation-era world. Upon deeper reflection, the ‘game’ is anything but.

Petscop dropped into existence on March 12th, 2017. The first video, titled “Petscop”, was uploaded by the channel of the same name. It opens with the classic PlayStation start-up, lending credence to the nostalgic aestheticism Petscop excels at. The Let’s Play’s narrator, Paul, then addresses someone off camera, stating that this is “to prove [he’s] not lying to [them].” Little else is known about the ‘lost’ game, other than Paul had ‘found it.’

After a few minutes of basic Pokémon-lite pet-catching and exploring, Paul enters a cheat code from a note that came with the lost game, descending Petscop into literal and figurative darkness. Following then on, the web series takes on a life of its own, with shadows of survival horror. The sudden transitions into darker storytelling, the sense of the unknown, as well as commitment to a show but don’t tell attitude, squares the series away into the timeless precedents of good survival horror storytelling. Viewers soon grow anxious over the fate of Paul himself as Petscop’s horror begins to seep out of the screen.

While the enticing story of Petscop is uniquely interesting, it is better experienced first-hand. Currently in 16 parts, equating to roughly two hours, the last upload in the series came on October 31st, 2018. The web series is a visionary way to utilise YouTube and the Let’s Play format, but the community’s reaction and passion for the subject is what has kept Petscop alive.

Of course, survival horror games often have cult followings. Pages and pages of discussion and forum posts still fill fansites for games such as Silent Hill 2, littered with theories, analyses and left-field experiences with the game. Petscop is no different. However, there is one critical difference between traditional horror fandoms and the community that has formed itself around Petscop.

Fans of survival horror games can play their beloved games and construct their own interpretations based on the subject matter. Petscop fans could never play the game as, well, it simply didn’t exist. Here, a gaming-inspired community formed around a ‘game’ that none of them could play but could still obsess over. How, then, did they combat this sense of fan disconnect? Well, they began to make their own re-creations.

The most popular of these remakes is the colloquially named Jamescop, now officially titled Giftscop, a community-led recreation of the game. The de facto face of this remake, James9270, had been involved in the Petscop community from the YouTube days. James explains that after he told an old work partner, named Elphont, about Petscop, they both shared an excitement for the game from a design perspective.

James’s tale started out as a continuation of a working relationship with his fellow hobbyist. Elpohont and James had “worked on several, small game projects in the past,” but both were enthralled at the mystery behind Petscop from a developmental perspective. The hook, to James at least, was how Petscop was “unlike many other ‘scary, mysterious game’ sort of stories […] what happens in Petscop seems like it’d be possible to do in a real game.”

Elphont agreed, so they both embarked on creating Giftscop for fun. Like many projects that are born out of a desire for fun, Giftscop ascended into something bigger. After James had posted some of their recreation progress to a Petscop Discord sever, “other people took interest in the project and offered to help. Eventually, it became a larger project than [he] originally intended [it] to be.”

Since that day, the Giftscop Discord server has grown. James and other developers, notably ‘red’, ‘Wirelex’ and ‘ugng’, share openly with its members about stages in development, bug fixes and new assets. The entire development is incredibly transparent, resulting in a remake that certainly feels like the source material. The remake has even seen several translations, while much of the current development is ironing out bug fixes and creating assets.

“A large portion of the work goes into creating assets, such as 3D models, sound effects, etc.,” explains James. “More recently, however, people have been translating the game into different languages: As of now, we’ve added seven translations into the game.” James and Giftscop have also borrowed assets from a previous, failed recreation, with the help of ‘red,’ speaking volumes for the interchangeable and open nature of Petscop’s remake community.

Matching Petscop’s faithful aesthetics, which James highlights as one of the major successes of the source material, has been difficult for the remakes, even for the talented hobbyists behind Giftscop. It appears that the “creating [of] assets,” which James highlighted as a difficulty, appears to be the sticking point for many remakes. “Some of the objects in Petscop are 3D models, while others are actually 2D images, positioned to look like 3D objects (possibly to allow for higher quality lighting than would be reasonable for a 3D model on the original PlayStation). Some (most notably, the characters) are even pixelated sprites.”

However, James and his team have found solutions through collaboration, a virtue that underpins all of these fan-made efforts. “The process of making similar assets usually involves someone trying to create one of them, and then posting their work onto the Discord server, and then other people either say that it looks accurate, provide suggestions, or make their own changes to it,” James describes.

This community spirit of giving didn’t start with Giftscop. “One thing I find interesting about Petscop, is that, with as much works has been put into it, all of its original art, music, etc, the creators have not monetized it in any way whatsoever. Some people have mentioned that it could break the immersion if they were to put ads in it,” muses James, considering his own initial reaction to the web series. “It seems that the creators of Petscop are passionate enough to avoid financial gain if it allows them to make the series feel more authentic.” Petscop’s decision to reject financial gain has followed into the community itself, where remake creators follow their inspiration’s decision to create art for art’s sake.

This desire to create a tangible Petscop game has led to several other remakes being developed. In addition to James, we spoke to ‘Mon,’ who is working in a team to make different remake, entitled PS1Cop. Previously, this project was being headed by Bubble, who has since left the team.

According to Mon, the goal of PS1SCop is to give fans “the full Petscop experience by both letting them play the game on their PlayStation and through an emulator on a number of different devices.” The major differences between PS1SCop and its contemporaries lie in its scope; much like Petscop’s subjectivity, it isn’t limiting itself to one iteration.

According to Mon, there are three other remakes of Petscop currently in development right now, including the aforementioned Giftscop. The other two are Petscop 3D and Miniscop. In Mon’s view, “the Petscop 3D Remake doesn’t really have anything over Giftscop besides being publicly available,” and Miniscop is “a mini Petscop with cute graphics and no real purpose.” What is interesting about these different remakes is how their creators’ unique perspectives of Petscop’s story has led to a myriad of remakes, each uniquely different despite having the same source material.

The overlaps between Giftscop and PS1Scop are also found within the community. Much like James, Mon explains that “[everyone’s] been supportive of the idea of PS1Scop,” despite a few reservations arising from PS1Scop’s closed-door policy. Mon has a clear respect for the asset creators in the community, too, whose contribution “should be credited” more than they are.

Unlike James, Mon’s deep-dive into game development was a “spur of the moment thing,” inspired by their sheer love of Petscop. Mon’s love of Petscop is, much like James’, difficult to elucidate, but words eventually come. “I think about the series every day” Mon says, inspired by “the people who created it and what their intents could be, and what it would be like to work on the game/series alongside the team. What process they go through to create an episode, and the communication between each member.” It appears that this implied sense of teamwork from Petscop’s original developers has been replicated in these remakes, a work ethic and positive philosophy translated by the work alone.

The captivating story behind Petscop is how its community, or rather separate communities, have united and divided over their collective desire to make a tangible Petscop game. The fact that so many recreations have popped up speaks volumes for the thematic depth of the source material and its ability to be experienced, and therefore recreated, in a myriad of ways.

Petscop is, in its fiction, a game that is alive, but in the real world, it is a game brought to life by its community. If that community keeps discussing, arguing and creating, then Petscop is sure to be reborn.