Walking Simulators Are Pointless – Here’s Why That’s Beautiful

Walk this way.

At the beginning of March, a discussion sparked on Twitter on the accuracy of the genre-label ‘‘walking simulator’’. Did this phrase accurately sum up the games within it, or were we doing a disservice to games like Dear Esther and What Remains of Edith Finch by reducing them to this phrase alone? As often happens, the topic then spiralled into whether these games were of value at all (an admittedly far older argument), with short runtimes and a lack of game-like elements such a puzzles and platforming making the experience less satisfying for some players. These questions were posed, but as always with a topic that is so subjective, no real answered were reached.

https://twitter.com/HelloMylesHere/status/1109270866360066049

‘‘Walking simulators’’ tend to fall into two distinctive camps according to how they engage with one element: narrative. While games such as What Remains of Edith Finch and Tacoma introduce you to a world immediately framed by previous human experience, more psychedelic experiences such as Proteus and Shape of the World leave the interpretation of the world up to you. It is those that have the least narrative direction that are often devalued the most. Yet, these games are often able to be more creative precisely because they lack a constrictive narrative, creating an experience that allows players to revel in just existing within a totally alien world.

What Remains of Edith Finch and Tacoma, like all walking simulators, have you floating in a first-person perspective, walking slowly through a new world. In both games, the short narrative established at the beginning gives a purpose and a role within that world, immediately focusing the perspective of the player to a particular mood or objective. Interacting with the environment in a non-strenuous fashion (no major puzzles or hurdles) lets you uncover the importance of this location, framed by the events that occurred within it. If you can imagine that all games start with the question ‘‘what’s the point?’’, these two give you your answer very quickly: ‘‘to find out what happened here.’’

In sci-fi adventure Tacoma, the answer to ‘‘what happened here?’’ is some pretty bad space stuff. In each new room the player explores, digital impressions of the previous inhabitants pace the halls like ghosts. By engaging with a computer panel, the player can play back the last scenes that took place there, re-winding and fast forwarding, choosing which side of the story to listen to according to which character they stand closest to. What unfolds is both the minute details of their everyday life and relationships with one another, as well as the overarching narrative that leads to the crew’s last moments on board.

Your experience of walking around the ship thus becomes a re-enactment of the previous character’s experience, like walking through the fog of time. The player’s exploration of this world is therefore completely wrapped up in finding out what happened, and the world becomes merely a backdrop to the lives of these ill-fated people.

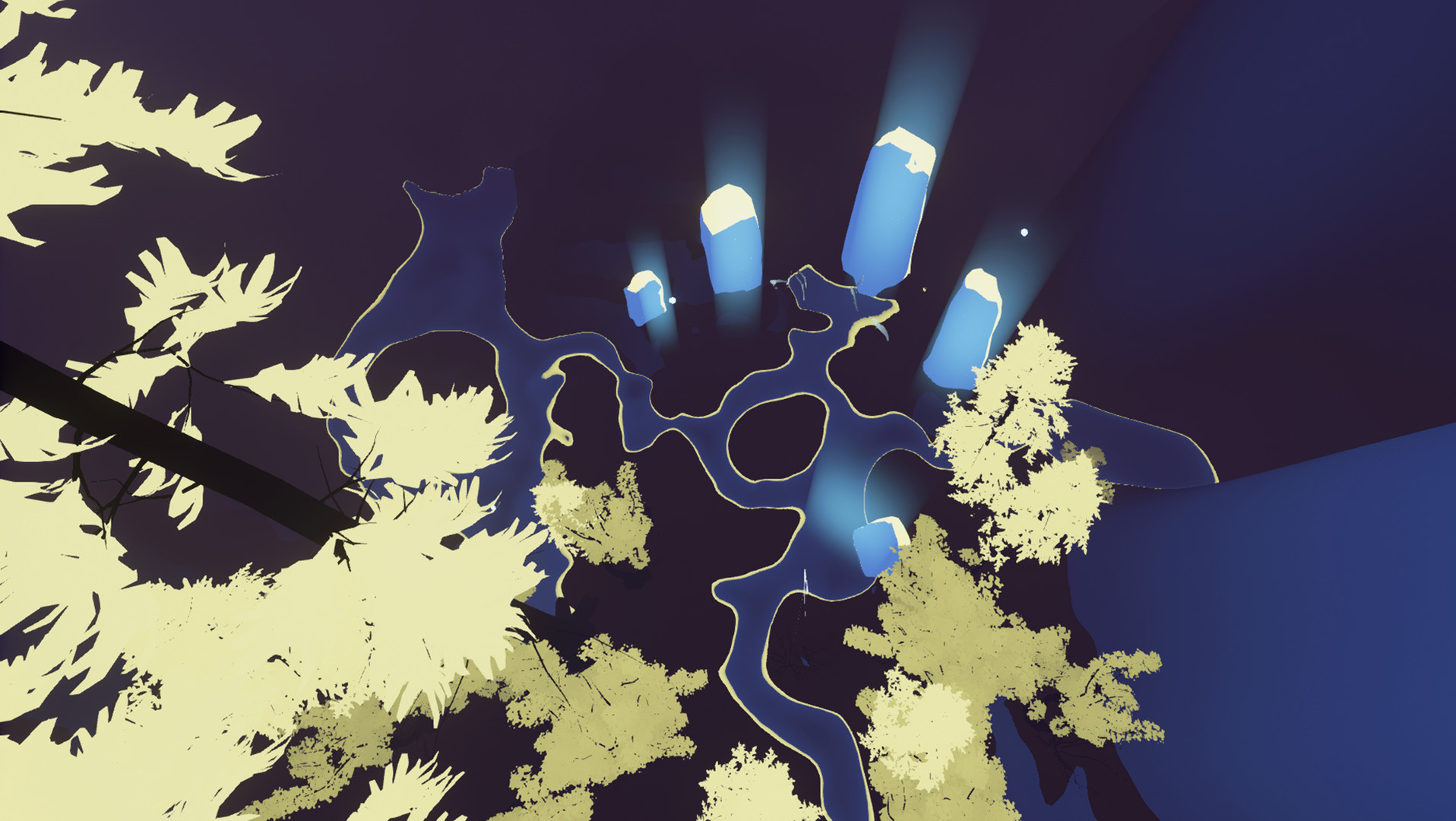

In walking simulators that remove the burden of narrative, environment takes centre stage. These are the games that answer the question ‘‘what’s the point?’’ with ‘‘figure it out yourself’’. Proteus and the more recent but very similar Shape of the World are perfect examples of this. In these games, you really are just walking around, but the act of observing becomes a game in itself, seeing not how you fit the world but how you fit into it. No real discovery awaits you, and no narrative prescribes your location; this is for you to interpret, and in no real rush. Here, the senses are allowed to take over. What a relief to play a game that demands so little of you, whilst giving you so much back.

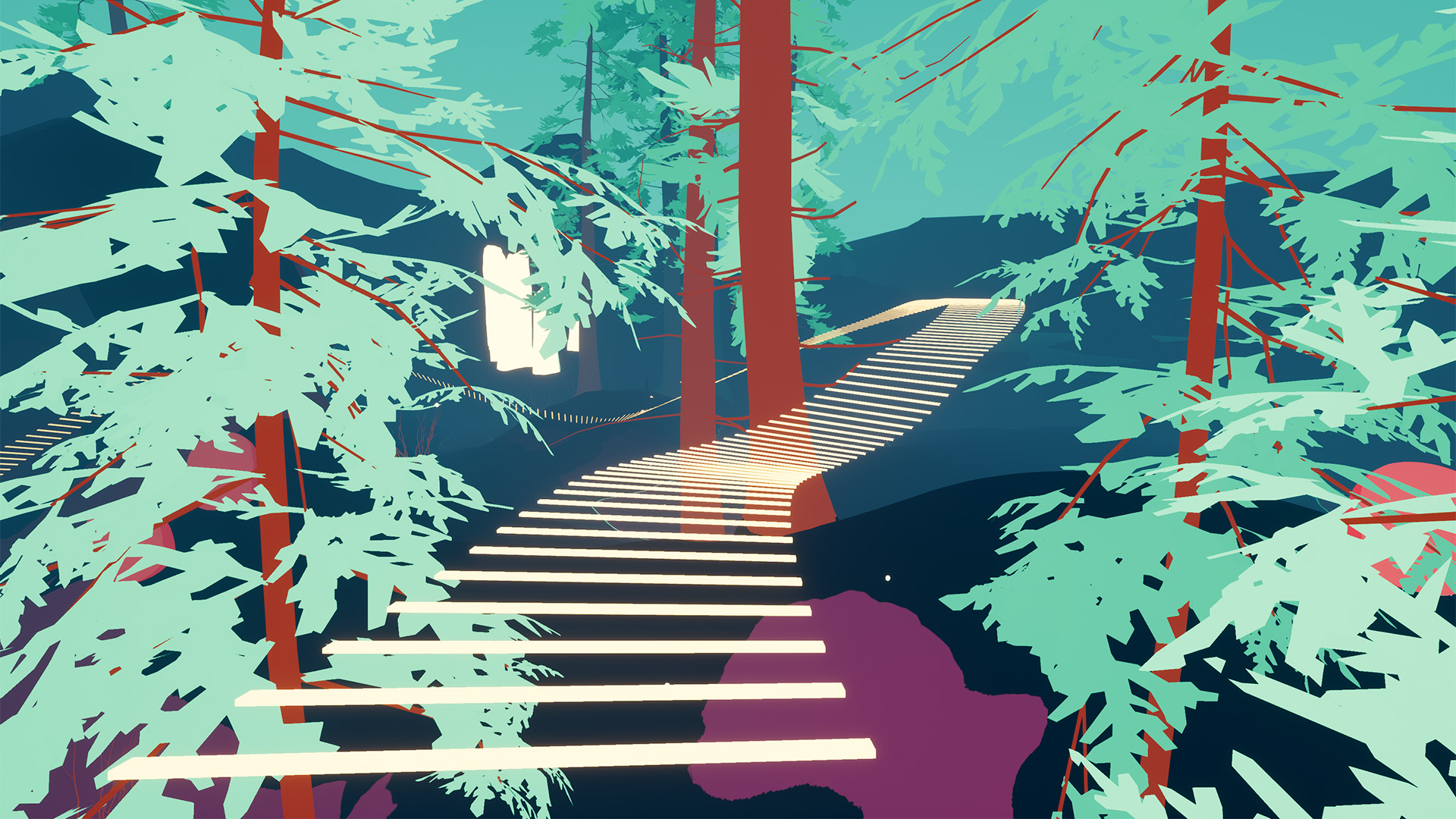

As you move in Shape of the World, mountains spring into life before you, new creatures scuttle past, and long grass appears that when tapped, bolts you a further forward. Movement and the way it affects the environment is king here, and while small puzzles do exist, mostly the joy is in the simplest of experiences: moving. Like a colourful playground, you are always in motion, whether or not you’re catapulted to a new area, flung up some stairs or nudged off a cliff by a disgruntled snail-like creature.

Once you’ve gotten over the initial need for some kind of progression or aim of existence, games like Shape of the World are incredibly rewarding and relaxing for their very lack of structure. There is nothing to be solved, or discovered, or fought and won, and what a luxury that feels like.

The broad nature of the term ‘‘walking simulators’’ allows games to constantly test the boundaries of what this might mean. With perspective and movement linking games in the genre, it is up to players whether or not they prefer an interactive narrative experience or something more ambient. While narrative aids experience, sometimes observing an artful and constantly shifting world is enough. As long as you’re moving, you’re experiencing something – who cares if there isn’t any point?