A Family Business: Game Dev Hell or Supportive Haven?

Your therapy will be my entertainment.

“I like to believe that developing the game turned out to be the final step in our own therapy and helped us to accept some of the unfortunate events we had to deal with.” – Iñaki Díaz, Appnormals (STAY)

We all know how challenging game development can be. Teams large and small have to be streamlined in their co-operation, often working under intense pressure in order to realise a creative and technological feat. The power of game development crunch to make or break a relationship between developers is immense, so what happens when that relationship predates the game?

When the idea for an article about family-run indie game development teams arose, one of the first developers we wanted to talk to was Appnormals, the minds behind STAY. We knew that co-founder and Art Director Iñaki Díaz and his girlfriend and screenwriter Ana had gone through a lot together, and that much of it was translated into their point-and-click thriller released back in May 2018.

We wondered how special, unique, healing or even damaging it could be to develop a game with your own family members. And what we found was that, for the most part, it’s all about support – having each other’s backs and going through heaven and hell together. There’s a kind of symbiosis between developers when they are working with shared backstories, traumatic experiences and hard times. There are many cases like these, and we’ll take a closer look at a couple of them.

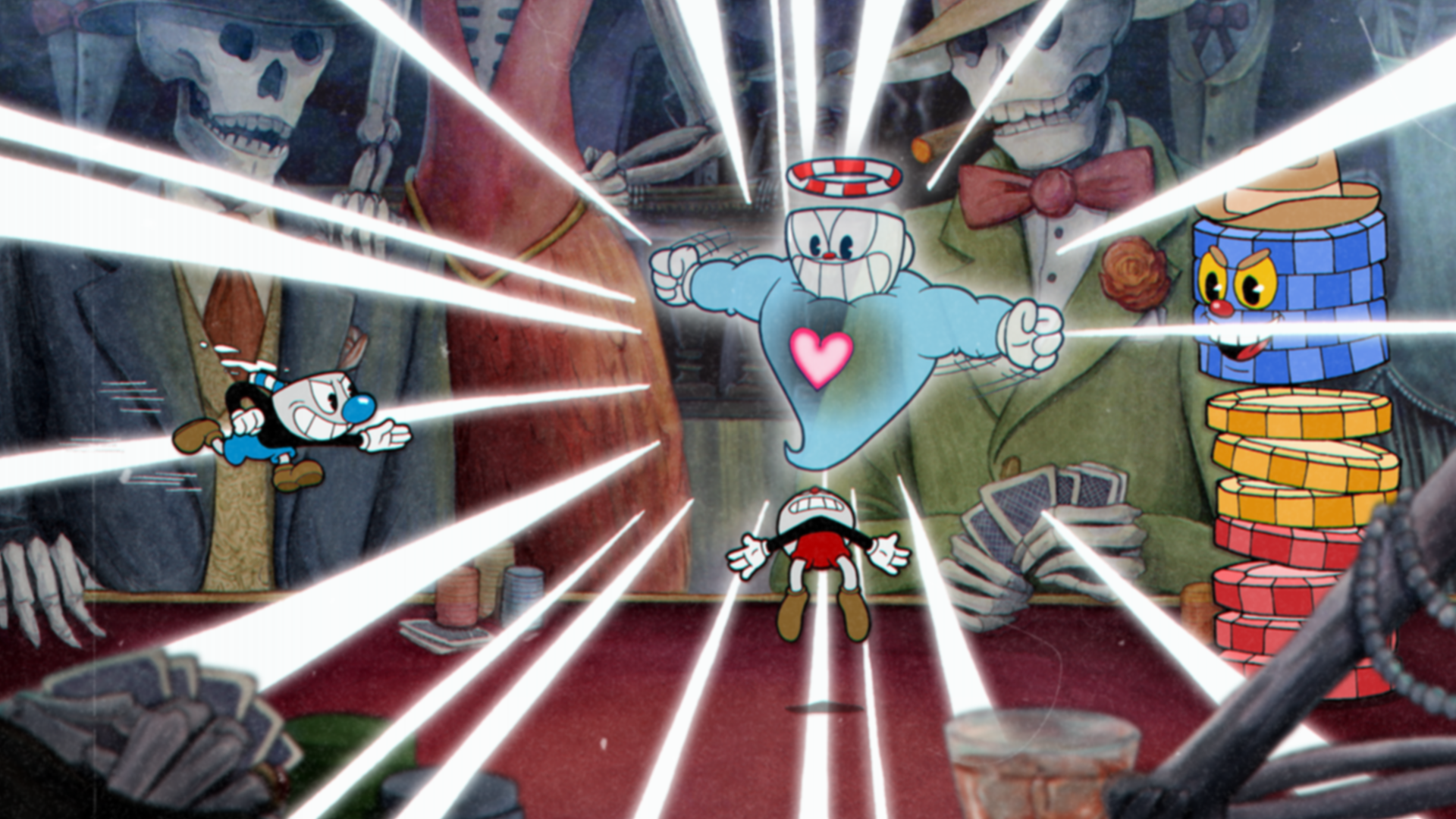

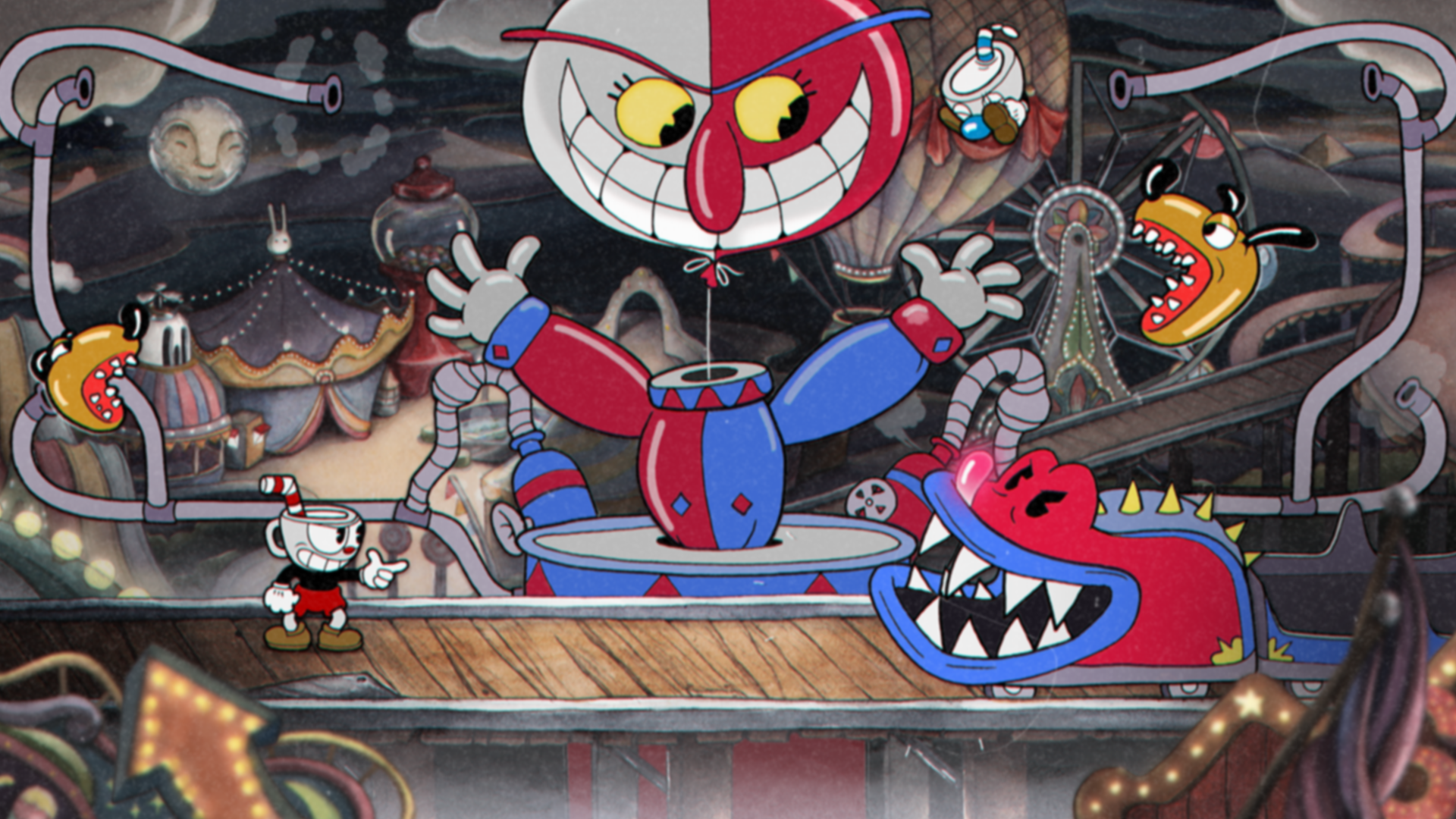

A recent documentary showed us the backstage of Cuphead’s development within the Moldenhauer family. “There was the reality at the end of the day that it could totally flop,” says Marija Moldenhauer, remembering the rough times they went through in what was, at least at the start, a “passion project.” That passion project recently hit the 3 million sales milestone, but we already knew it was a smash hit way before that.

The idea that a family invested so much and put so many things at risk (like their future) to develop a video game might make all those non-believers of this medium out there reconsider what all of this means.

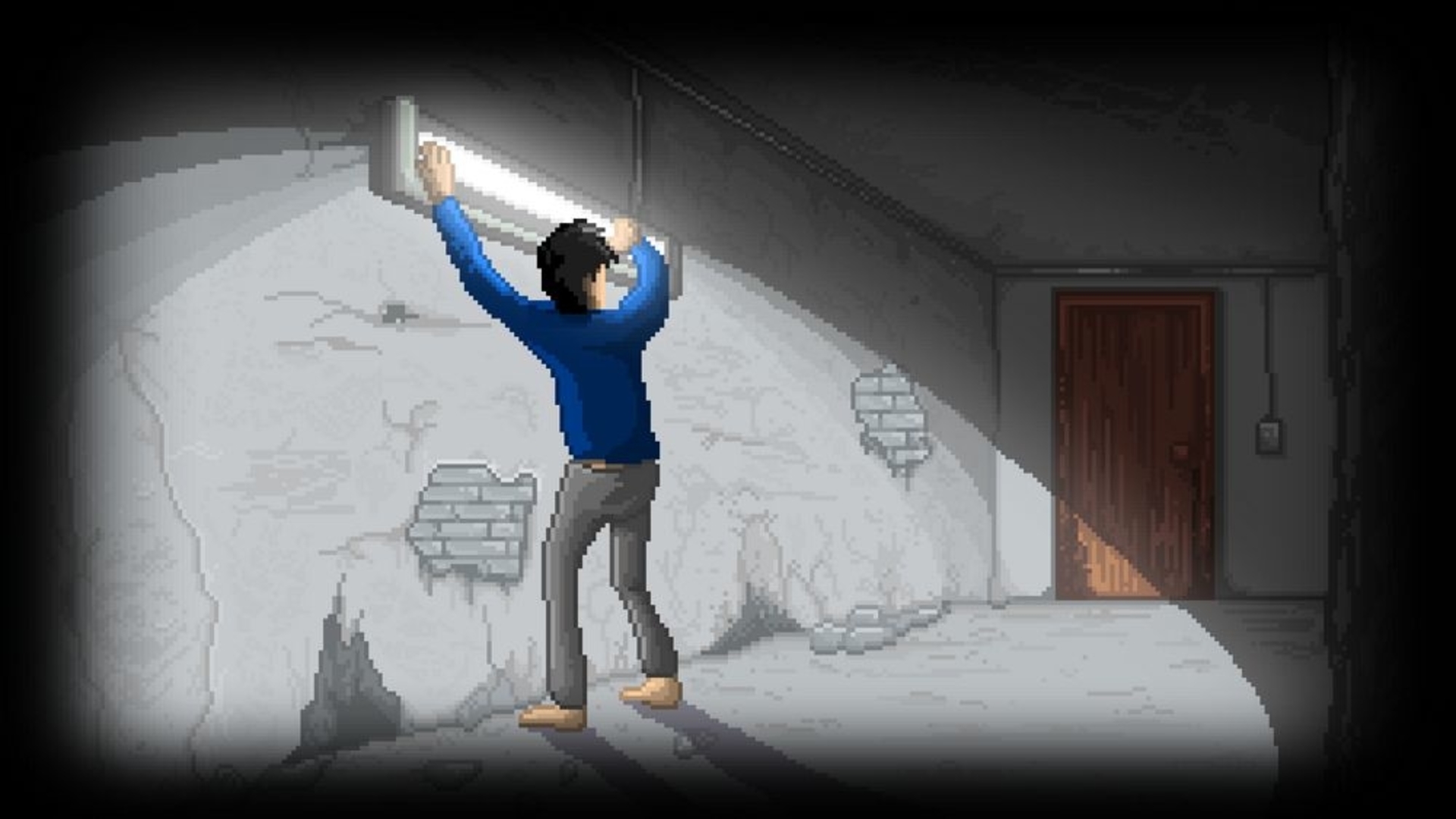

Back to the first line. “I like to believe that developing the game turned out to be the final step in our own therapy and helped us to accept some of the unfortunate events we had to deal with,” Iñaki Díaz from Appnormals tells us. This game tells the story of a young therapist who wakes up imprisoned in a dark basement, left alone at the mercy of his depression and anxiety. But what hides behind the curtains of this show is much bigger, and we may never know the whole story.

“Without completely disclosing the reasons behind STAY story-wise, it is a game that came from a personal experience that both Ana (Iñaki’s girlfriend) and myself went through a few years ago. So it was basically a thriller based on a very intense period of our lives translated into a game. Somehow we needed someone able to translate these emotions into words, someone capable of re-living that period from a creative perspective.”

Sound like therapy? It was.

And as tough or far fetched as it may sound, it does make sense to approach a traumatic experience from a new standpoint, a more creative one, less damaging. There’s no way to know what these developers went through as a couple, but it was certainly powerful enough to urge them to transform it into something they could show to the public. We all know that sometimes we just need to find a way of externalizing what we’re going through without revealing the whole truth.

Appnormals came up with some concepts and poured them into a thrilling tale like the one we can experience in STAY, a claustrophobic thriller in which we act as the lifeline for the main character. Players can only communicate with protagonist Quinn through a chat window. We are his only hope and he doesn’t even know us. “All our fears and struggle were reflected in the game,” Iñaki explains.

On the other hand, we have Butterscotch Shenanigans, the studio behind Crashlands. Led by Seth, Sam and Adam Coster, their story is a bit more uplifting. From what they’ve told us, they seem to have a lot of fun, but trust is the main concept that transpires from their story. It’s all about history and trust. “If you’ve got good family ties, there are few better business partners to work with,” says Sam Coster in conversation with us. “You know they aren’t going to do something to deliberately hamstring you and that they’ve got your interests in mind, because if they don’t then you’ve got 60 years of awkward family encounters to look forward to!”

You said it, Sam. Imagine your brother, Mom, Dad, sister or other family member taking liberties on a shared project. It doesn’t even have to be severe; modifying a character balance or stat without asking, for example. How would that turn out? Maybe you don’t talk about it until it somehow explodes.

In a professional workplace, we can go home to our families, seek external advice, and come back to work the next day refreshed. Even if we’re still bitter about it, most workplace disputes can generally remain at least professionally amicable after a fallout. But we all know it’s pretty much impossible to remain purely professional when in a working relationship with family members. There’s a lot more on the line when difficulties arise, damaging your relationship.

Iñaki’s opinion is that “it’s nearly impossible to keep the relationship composed during hard times. For instance, you’re certainly going to suffer the consequences from natural anxiety when looking for funds or before launching the game.”

Butterscotch Shenanigans, however, found that the familial ties helped streamline their team’s communication. “Having grown up with one another we have a really good pulse on how people are feeling,” says Coster. “It’s much easier to have those tough conversations about work, life, and everything in between because we’ve got a ton of historical material to pull on.” And while true, it obviously depends on what kind of relationship you have. But it’s clear that the Costers have a strong foundation and their studio is built on good vibes.

But even for Butterscotch there’s something that doesn’t change: achieved goals are nice, but failures become much more serious. Sam Coster mentions the “deep feeling of success you get from pushing not just yourself, but your family forward.” But when things aren’t going so good, the mind panics at what the consequences could be. This was very clearly described by Studio MDHR’s Marija Moldenhauer when she confessed that during those days without sleeping while developing Cuphead, “it was just survival. You had to get up, you had to work,” she says, while remembering those times when her newborn’s future was at stake.

But how big is the difference between developing as a family-run studio compared to traditional teams? For the Coster family, it’s all about faithfully representing what they had in mind as a unit. “It has to respect the shared history and ties of the family building it, long after the game has shipped,” says Sam. It makes sense. Imagine wanting to tell a deep, shared story and the final product doesn’t feel right for one of the studio’s members on which the experience is based.

For the people at Appnormals, the difference lies in the financial risk. It’s not just that the studio may not reach its ROI goal. “When all the family income is bet on the same project, the risk is obviously higher and so the need for the project to be successful in some way”, adds Iñaki. “On the bright side, no one knows you better than your partner, especially when you have been together for more than ten years.”

Cuphead has sparked inspiration for a number of familial game development teams, and with the indie community being such a connected one, it was only a matter of time. Sam Coster talks about MDHR as an inspiration for Butterscotch by saying that “Cuphead is one of those wild successes brought to life by a family team, it’s something we’ve cast an aspirational eye toward.” On Appnormals’ side, Díaz also compares their situation with Cuphead’s: “Although they dealt with a way bigger project (budget-wise) and equally gigantic potential consequences in case of failure, we obviously relate to the main fears and concerns.”

Developing a video game is not the everlasting party some may imagine. Much less so when your future and financial stability are hanging from a project in which your own personalities and personal experiences are reflected. Add to that a highly personal development process itself, and there’s definitely room for catastrophe.

And to think that those experiences and pivotal moments of your lives are going to be translated into something people will play with, something users are going to use as entertainment for a little while in their life. It’s therapeutic, it’s cathartic and sometimes fun, but it’s also a game, and adding all the pressures of traditional game development into the melting pot can make or break a team.