We got an archaeologist to review The Bradwell Conspiracy

Here’s what they thought.

My biggest fear going into The Bradwell Conspiracy was that at some point I would encounter the remains of an alien spaceship, or perhaps just little green people hanging out at Stonehenge. Not because this would be inaccurate (even for an archaeologist like myself, some speculation is entirely forgivable), but because it feeds into bigoted ideas about ancient monuments. After all, if you think its more likely that mysterious intergalactic beings built the pyramids rather than ancient Egyptian ingenuity, you might be less imaginative and rather more racist than you thought. Spoiler alert: The Bradwell Conspiracy probably isn’t about aliens, but it isn’t really about Stonehenge either.

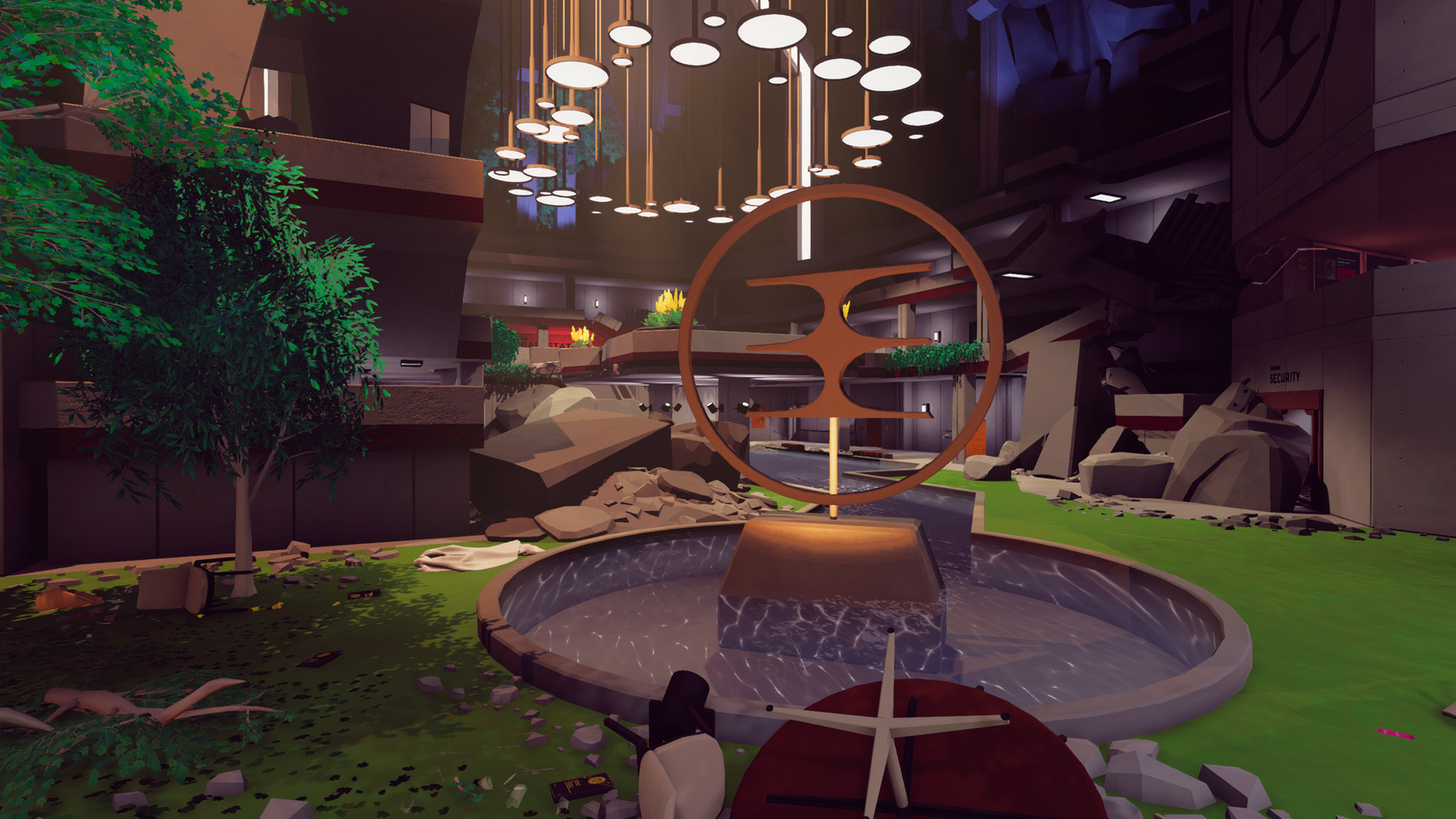

Before I dig into the archaeology of TBC, let’s set the scene. It’s 2026, you’ve just regained consciousness after an explosion at the Bradwell Stonehenge Museum, and you’re locked inside. Luckily, you’re not entirely alone. Using the Bradwell Guide Glasses, you photo message with Dr Amber Randell who also didn’t get to ‘exit through the gift shop.’

Speaking of gift shops, it strikes me that TBC can be compared to one of the Historic England branded gifts available in their online store: a Stonehenge jigsaw puzzle. Just like the 1000-piece puzzle, TBC uses Stonehenge as an aesthetic setting for its many brainteasers, the irony being that despite much of the game being set in a facility underneath Stonehenge, the consideration of the World Heritage Site is only skin-deep.

The game can be classed as a walking simulator, but its puzzles certainly aren’t a walk in a park. My greatest criticism of TBC is that said puzzles are often challenging not because they’re actually difficult, but because they rely on you standing in exactly the right place and rotating an object which may seemingly not work for an arbitrary reason. The game’s key mechanics clearly draw from its two obvious inspirations: Firewatch and Portal.

As the anonymous and silent protagonist (your lungs were damaged from smoke inhalation) you need to send pictures of your surroundings to coordinate with Amber. I enjoyed using this feature more than the Substance Mobile Printer, which is essentially a 3D-printing gun that allows you to spontaneously materialize objects that you have the blueprint for. Whilst the SMP might sound like a flashy gadget, its implementation in the game is often tedious.

Circling back round to the Bradwell Stonehenge Museum, the initial stage of the game was perhaps my favourite. I was amused and disturbed to discover that in this version of the future, the planned A303 tunnel under Stonehenge had actually gone ahead. To give some context to this, the potential tunnel has been argued over by archaeologists for years, so to see this alternative history in a video game museum setting was uncanny.

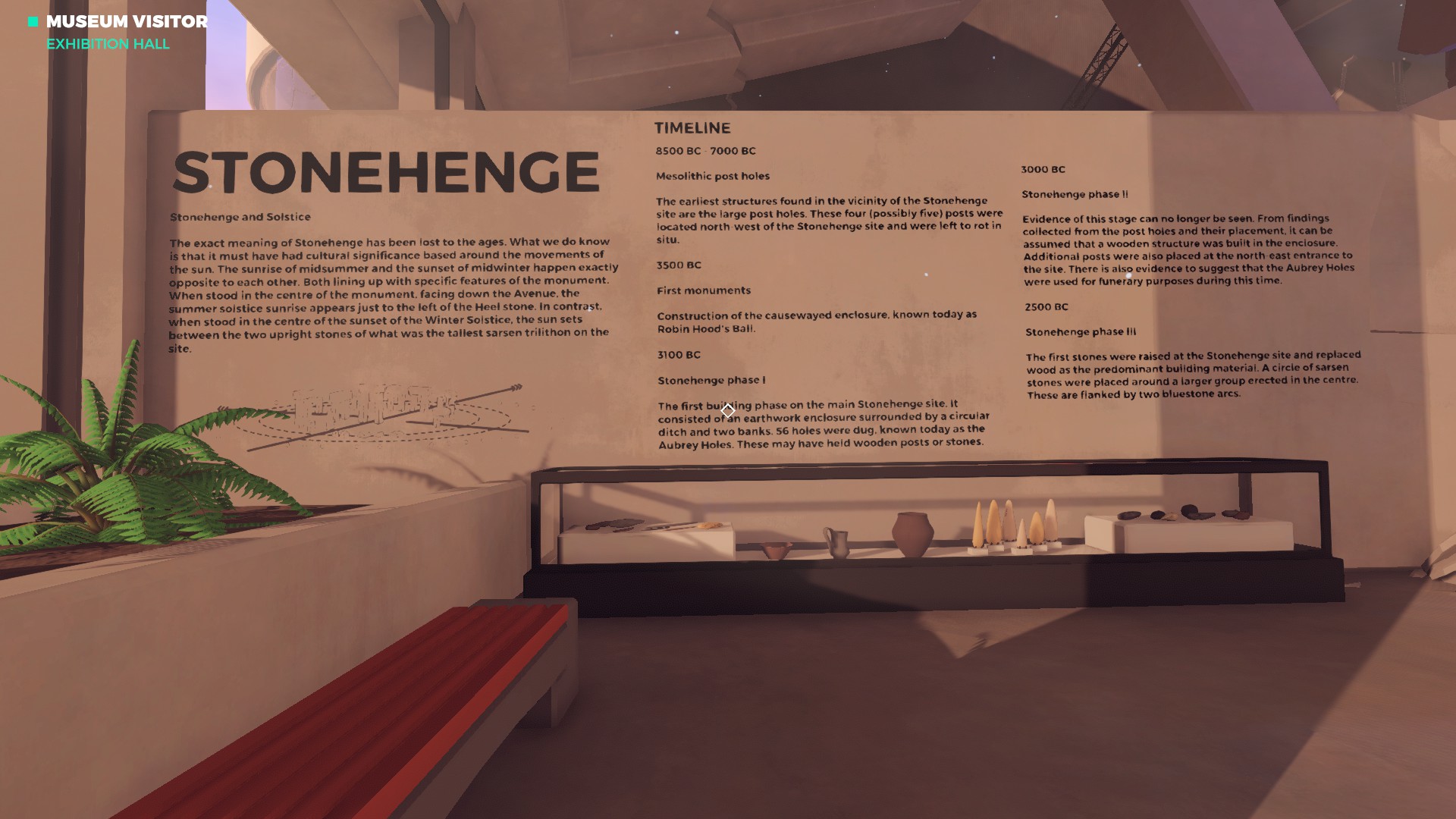

Most unsettling is the realisation that Stonehenge was taken under the stewardship of The Bradwell Foundation and Company Group when the British government was unable to maintain the site. We’re also treated to a small exhibition space with low-poly rendered prehistoric stone tools and pottery. An accompanying wall display gives a simplified timeline of the Stonehenge site that abruptly ends in 2500BC, one of many indications that the developers could have benefitted from more time.

TBC may not really be about archaeology, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t archaeological. Like many walking sims, much of the gameplay involves exploring an environment and learning more about the people that occupied it through the material culture they’ve left behind. Melissa Kagen of Bangor University coined the term ‘archival adventuring’ for this kind of gameplay.

I loved discovering peoples’ redacted letters, scrawled meeting notes on whiteboards and even finding an unfinished card game abandoned during the evacuation. These subtle details are more effective for ‘reading a room’ than the sometimes tone-deaf commentary of Amber over the Bradwell Guide Glasses that start to grate pretty quickly. One other detail that I really appreciated: a crucial setting of the game is shown to be wheelchair-accessible for a character who lived there.

I can’t say much more without digging myself into a deep hole of introspection, but its fair to say that TBC touches on a lot of timely concerns but doesn’t have the wiggle room to delve further. As far as I’m concerned, the game is a parable on the arrogance of exploiting heritage sites. Back in the early 20th century, Stonehenge was actually bought from the Antrobus family and ‘gifted’ to the nation by Cecil Chubb. Let’s hope that life won’t imitate art and the great lithic monument doesn’t end up as an expensive ornament for a rich family.

[Reviewed on PC]