Per Aspera Review

A few hours into Tlön Industries Per Aspera, I started to get the feeling that it was well and truly under my skin in a way I had not anticipated. Touted as a city builder with a narrative that has you uncover twists as you go, I was not expecting the real core of the game to be a hard science story that probed the meaning of self, and perception. On the surface, this is a game about building a self-automating base on Mars, shipping in colonists from Earth, and terraforming the planet to sustain life in the future. 50 game years into the game, it is about dealing with Bicameralism, long-drawn political posturing, the cost of human life, and what it means to be an AI.

It’s complicated

It’s hard to really sum up the whole of the game neatly without betraying half of it. Much like the bicameral mind, it is a game of two halves: one half has you do, the other has you listen. The doing is simple: you play as AMI, a bleeding-edge AI tasked with something arduous terraforming Mars.

You start with a small base Mars, and after being given orders by ISA professor Nathan Foster you begin mining and refining a series of resources across the surface of the planet. You eventually form Anno style supply chains that let you expand your base further, turning iron and carbon into steel, steel into machine parts, machine parts into drones, and so on.

Breaking the mould

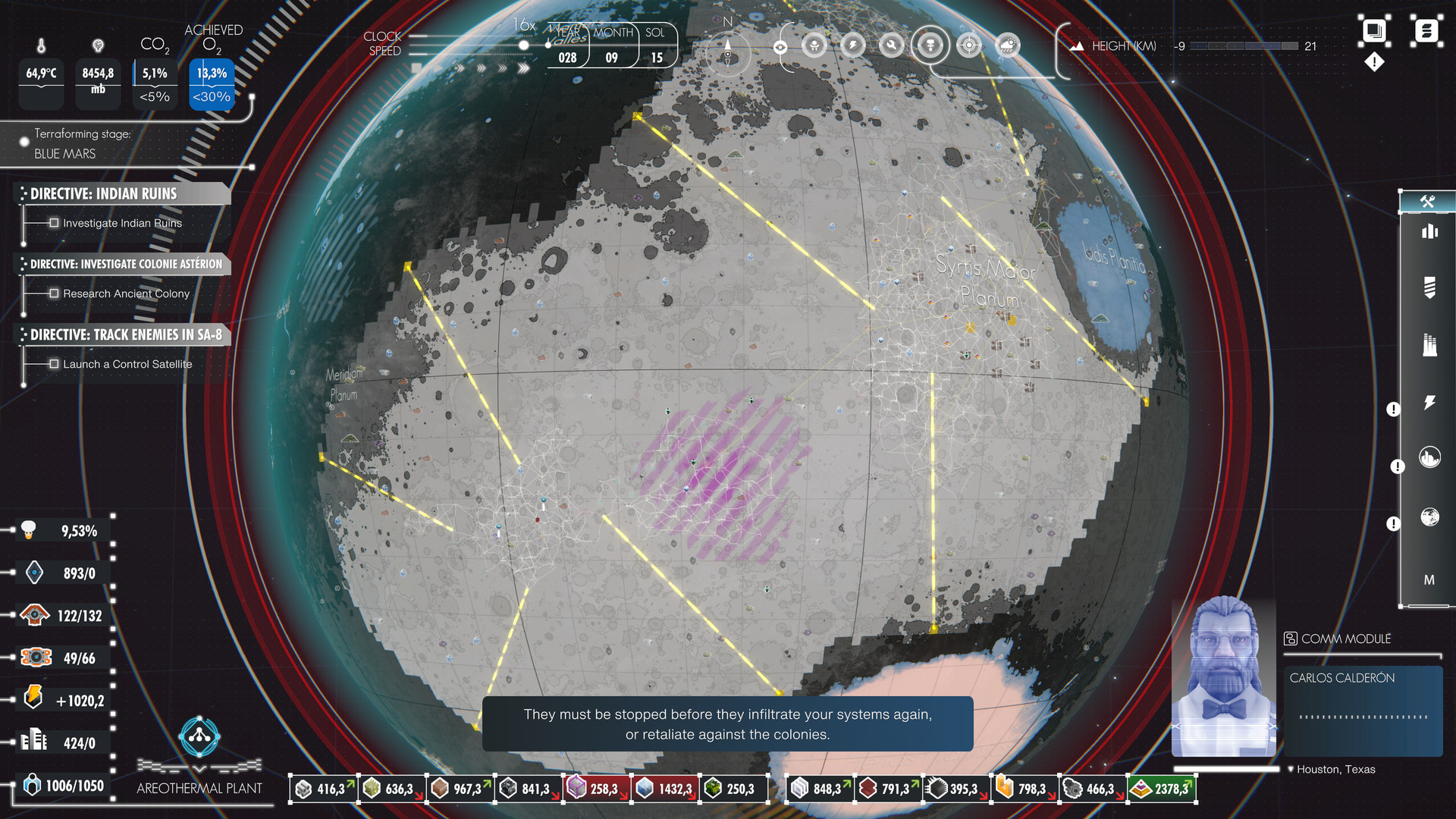

Every building you place down thrusts out slime mold-like tendrils, working out the most efficient way to connect to the growing spider web of mines and resource hubs. Over time you spread like a fungal growth across mars, creating bigger self automating networks, connecting hyperloops and spaceports to your main clusters of resources, changing the planet irrevocably in the process.

The narrative elements start to come in more heavily when you are given options to explore and research various routes to terraforming – do you use the nukes left by previous expeditions to melt the polar ice caps, or do you try less destructive methods such as mirror arrays and asteroid braking?

When colonists arrive on Mars, and mysterious malfunctions and attacks start to occur, how do you respond to them? What story do you tell your handlers? To the game’s credit, the narrative is rich and well told, with interactions presented in a visual novel style, and acted with a level of professionalism that wouldn’t seem out of place in a AAA release.

More than a feeling

Troy Baker is well known for his multitude of roles, but his heartfelt performance as a scientist trying to nurture and guide AMI is perhaps a career-best. Phil Lamarr is exceptional as the acidic Lt. Carlos Calderon who intrudes in the running late game, and Lynsey Murell gives an understandably emotional performance as the leader of the Mars colony under your protection. Yong Yea’s Nian Zhen also throws a spanner into the work, revealing the ISA to be part of the Oxy UN, an organisation that has no ties with China and the East. The further the rabbit hole goes, the more tangled the web of players and the timelines become.

All of this would be impossible without Laila Berzins excellent portrayal of AMI; a newborn AI full of the naivety and confusion one would expect. As you interact with characters more, and as the game expands, revealing new challenges and mysteries, AMI grows in interesting ways, guided by your choices as the player. You never feel hemmed in by your decisions, and much of your navigation through the story will see you decide whether to elide certain truths, or prioritise certain factions or narratives as you make decisions. If anything, Per Aspera positions the player as the right half of the bicameral mind, speaking decisions into the left half that plays out on screen.

The story inevitably leads to combat, which is sadly the most underbaked area of the game. It sees you construct automated drone hives that act in a tower defence style. It’s never granular enough to feel worthwhile investing in, and your drone forces require too much micromanaging for an all-powerful AI.

That’s just a lot

In a similarly frustrating manner, the resource systems can get fussy at times, with resource and maintenance drones not being as smart or efficient as you might expect, and upgrades to resource buildings feel redundant at best and punishing at worst as materials become hard to source later on.

Toward the end, the story diverges in a manner which will have fans of hard science fiction stories cheerfully surprised, and in my 20+ hours, I discovered at least three major endings you could reach via different choices to one important late-game decision. These choices don’t play out in radically different ways – the end goal for all of them is always to complete a large scale resource crunch – but they do position you in very interesting narrative circumstances, which is ultimately worth more than tweaked mechanics.

The end game grind and overall lack of granular control over certain elements are endemic of the game’s biggest problem, which is that both its simplicity and complexity brush together in awkward ways.

Which way is it?

It is frequently unclear in the requirements and parameters for progression, which can at times be explained as your character’s POV, but at others, it’s a simple lack of clarity. There is also an ongoing issue with narrative chunks not arriving at the correct trigger, or with the right pacing, and the end game grind potentially being impossible if you haven’t lucked into a perfect set up for atmosphere production early on.

It’s a shame, as the wonderful simplicity of its visuals and interface that subtly reinforce your role as an AI by allowing you to change your “perception” of time by speeding up or slowing down time (resuming saved games by “waking up” is a similarly nice touch) lay the groundwork for a clear and concise resource management game, but Per Aspera is at time of writing not quite there mechanically.

All that being said, there’s a temptation to argue that this split between the simplicity and complexity of the two halves of the game is a representation of the fundamentals of a task as grand as terraforming, and the reality of its practical implementations. The narrative that dresses the gameplay is also meaningfully at odds with the mechanical at times, and in some ways, it feels much like the bicameral mind – it can speak the actions of a resource builder and a narrative game, but it is unable to use the former to listen on the latter in a meaningful way. A strict adherence to its systems undercuts the smarts of the AI (why is water from terraforming not able to be harvested during late-game resource crunches?) at the same time as it makes its compelling commentary.

I mean, I’m in

Despite all of this, it remains an engrossing experience – the clash between interior and exterior forces remains intriguing from the moment it is introduced, and it certainly gives players plenty of food for thought, if not a whole lot of mechanical crunch.

For those that want an in-depth city builder, Per Aspera is perhaps not the right game, especially as it constantly battles with the ethicality and morality of its very conceit. For those who want a rich sci-fi experience, the clash between the complexity of the problem and the simplicity of the mechanics may cause players to find themselves stuck in a progress bottleneck.

Regardless of these criticisms, it’s impossible to write off Per Aspera because it attempts something novel and is so close to sticking the landing that its namesakes seem incredibly fitting – “through adversity to the stars” -there are plenty of hardships here, but in the end, it reaches an unlikely, dazzling goal via its storytelling.

[Reviewed on PC]