Pendragon Review

Pendragon is a narrative strategy game from the makers of 80 Days, Heaven’s Vault, and Sorcery! In it, you are tasked with joining the legendary Arthur at his fateful meeting with Mordred – his bastard son, and ruinous King of Britain.

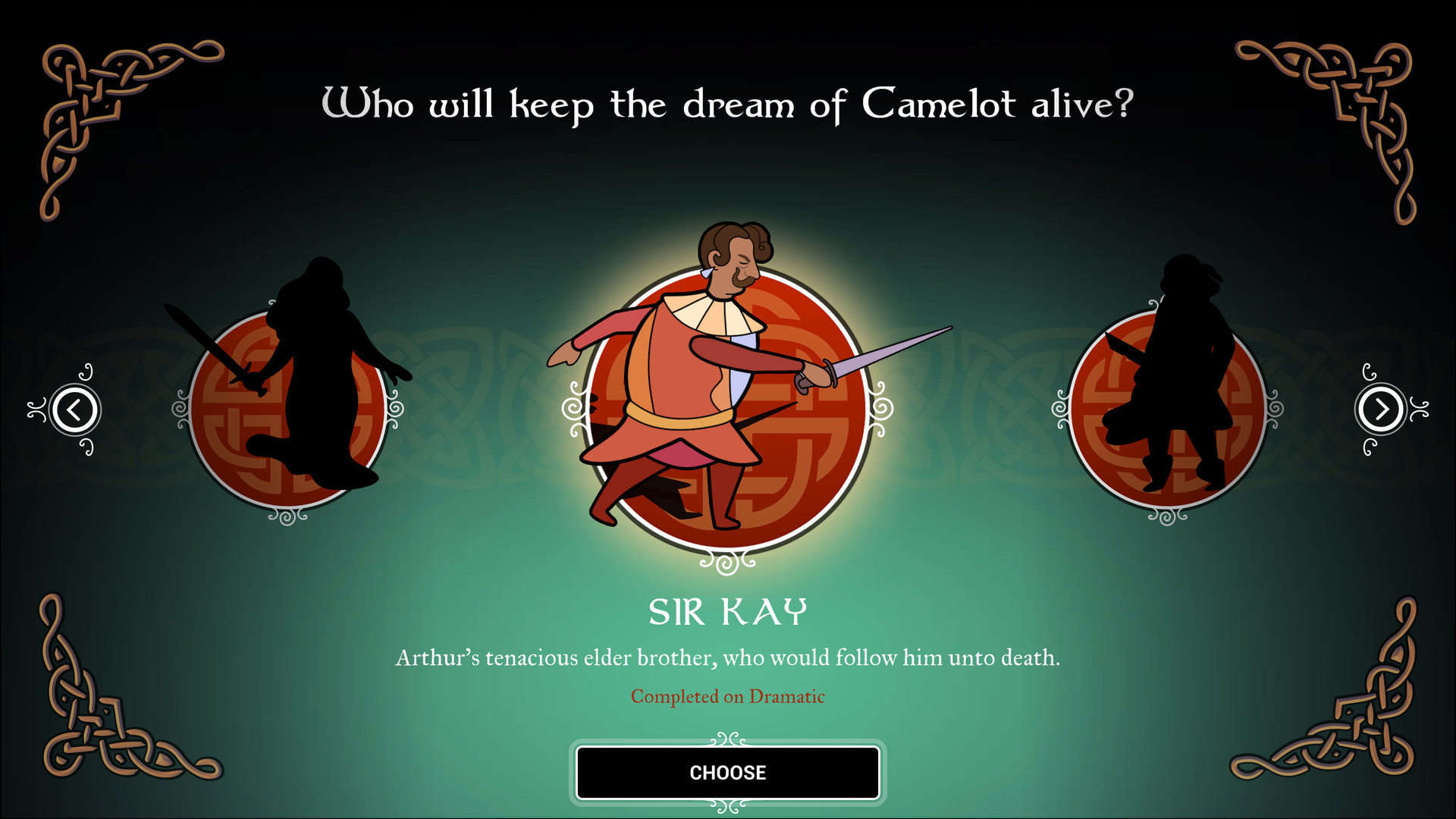

You lead the way starting as either Guinevere or Lancelot, recruiting and unlocking up to nine figures of Arthurian legend to fight alongside you on your journey north to Camlann, along with helpful knights and brave villagers who take up the call to fight. Or, if you’re me, lead as Guinevere over and over for a few hours after a recruited knight calls her ‘Guinevere the Fireproof’, after finding that so entrancing that moving on to another character as a leader seems impossible. After that, what is Lancelot going to offer me? Being French?

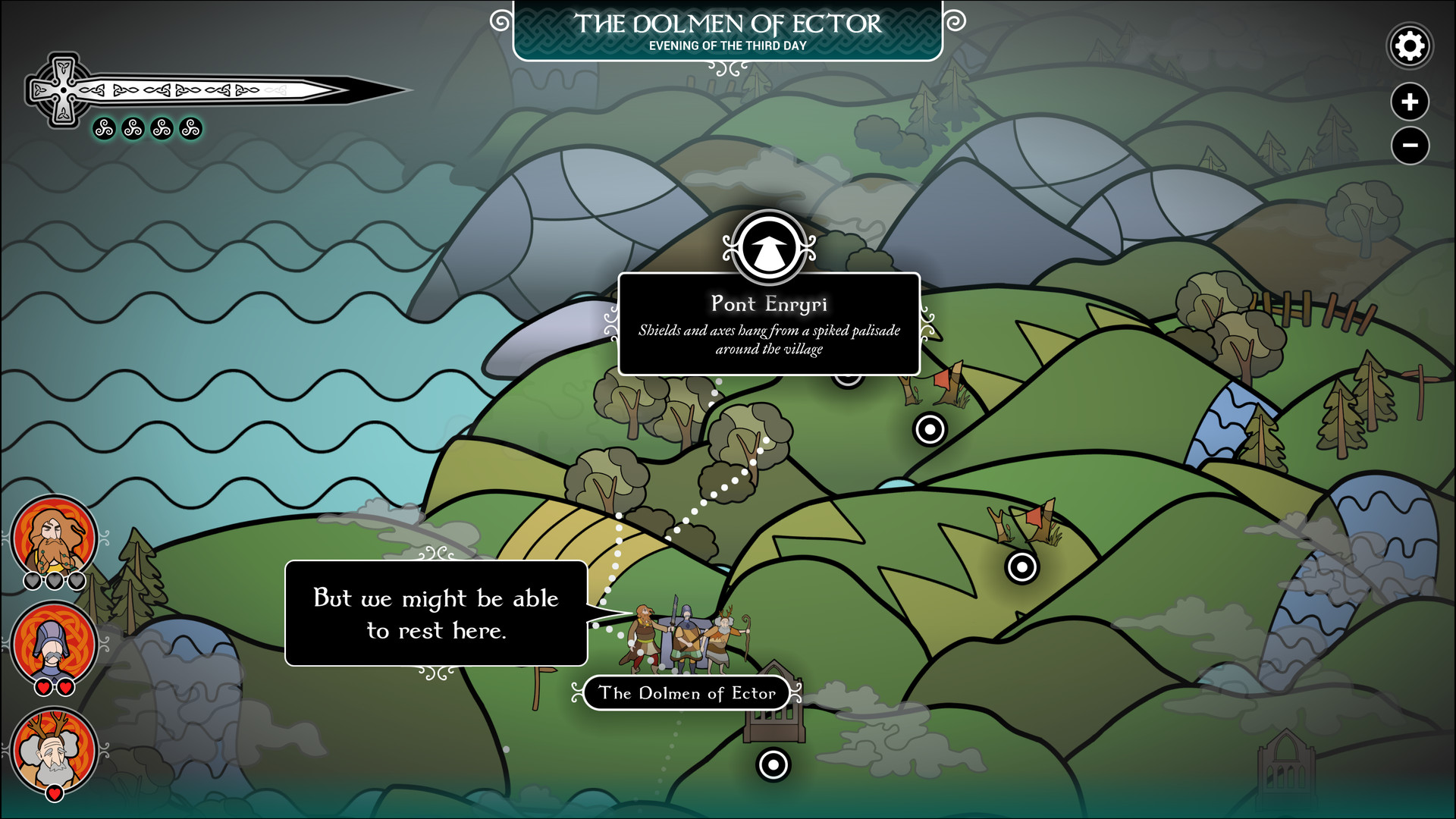

Pendragon’s hook is that its story is told in each beat of its gameplay. As you advance or retreat across the board, sacrifice or capture characters, the story unfolds with each moment, with no two playthroughs being alike. The gameplay is simple (though not strictly easy): In each level, your goal is to cross to the furthest opposite square of the game board, either defeating or evading your opponents on the board. Claiming squares manipulates mobility for both sides, and you can capture directly adjacent pieces. Pivotal moments for each character unlock new or changed skills, with some characters having innate skills, to begin with, that change your approach of play.

Chess with barks

It’s an ambitious hook that could easily have devolved into “chess with barks”, but Pendragon not only pulls off what it was aiming for, but tells stories about characters you can’t help caring about. Despite my long attachment to Guinevere, I eventually found that even Lancelot brings more to the game than simply being French.

A single run is short, even a successful one likely coming in at under an hour. Like previous inkle property 80 Days, which sees you attempt to circumnavigate the globe in an alternate historical setting, trying to race to the ‘win’ is less rewarding than the story along the way. While I did spend time trying to orchestrate wins under certain conditions, I never pushed to Camlann if I thought stepping sideways and spending the night in a mystery village might nudge along interesting conversation along between two characters. However, this might reflect on my preference to play at lower difficulties – more dedicated tacticians playing at higher difficulties might find they need to push to Camlann once it’s made available, in a race against the loss of provisions. Keeping the difficulty low meant I regularly found enough rations to keep my parties fed and morale high, so I could focus on specific pursuits.

Now, that is clever

Some stories can feel more authored than others, such as the fraught final showdown between Arthur and Mordred. However, it can’t be disputed that they all emerge the same way, between your moves on the board. It isn’t reading between the lines when I’m touched by the story of a villager who, after expressing his unrequited love to Lancelot, takes up his sword and cuts down the rogues who downed the Norman in a panicked do-or-die flurry, permanently exhausting some of his own health to do so – it’s explicitly in the text of the game. It might be generated by the mechanics, but the mechanics and the story are explicitly inseparable.

The flipside of this is that some parts of the game can feel a little awkward, when the game boards are used in atypical ways. Sometimes story happens where you don’t have an opponent on the board, and that leaves you clicking around to-and-fro to invite your characters to speak. These sections aren’t long, but it can feel strange to stop thinking tactically about your movement around the board for short scenes when the setting has primed you to do so.

Not a bored game

Pendragon does feel board game-y throughout, in a tactile sense. Characters only have two sprites: one ‘up in arms’ version, and one relaxed one. The style is very much that of game tokens, with each move across the board accompanied by a satisfying ‘clack’. It’s all the more impressive that such emotive stories come across with tokens that need to stand in for every scenario, but perhaps you’d be less willing to make tactical sacrifices if the trapping of board games weren’t so consistently in front of you.

This overarching risk of sacrifice fits into an earned sense of gloominess. In each run you strive for a heroic telling, but what if those don’t come without struggle? Many of the villages you come across are abandoned, landmark temples are crumbling and overcome by wild animals, and it is almost always raining. Sometimes your combatants aren’t part of the trained opposition of Mordred’s knights, but disenfranchised civilians who’ve chosen hate over resistance – or those who’ll oppose you simply out of the need to fleece you of belongings to sell.

That doesn’t make the story needlessly grim, though. However flawed your party members may be – and they are flawed – they carry on to Camlann because they share a belief in Arthur. They believe in each other, and believe in something better for Britain. It’s hope that moves the game forward, and mechanically speaking, it’s morale that keeps your pieces on the board, and resolve that lets them rely on each other and enact their unique abilities. Pendragon is built on balancing tensions that would break a lesser game to pieces, but instead creates something new and worthwhile in that space.

[Reviewed on PC]