From Meat Boy To Ori – How Indies Revolutionised Mascot Platformers

So many feelings

When I was a child, my first proper exposure to the world of video games was through a tried and tested formula – the mascot platformer. Big, colourful characters were often running and jumping their way through a series of levels to save a Princess or stop a maniacal doctor with a fabulous moustache. I was transfixed by the ever-expanding adventures of these larger than life characters. But as the 90s left and the millennium arrived, I and the industry as a whole started moving away from the genre.

There were many contributing factors to this; some of our beloved mascots didn’t quite stick the landing when making the transition to a 3D space, and the market had become saturated with cheap shovelware knock-offs of our favourite plumbers and hedgehogs ranging from radical dude geckos to an anthropomorphic glove (the 90s were wild). But the key factor to the slowdown in platformers was that we were ready for something new. Games with realistic graphics, worlds that felt tangible, characters that carried more guns than an NRA anti-quarantine rally. Stories that had stakes, gameplay that felt unique and challenging, aesthetics that had artistic fidelity and didn’t just pander to hyperactive children. The 2D platformer, outside of the big names, was left in the annals of history.

But not for long. A rampant and revitalised indie marketplace soon noticed the missed potential of the genre and reinvented it in new and innovative ways. Over the last decade, we have seen groundbreaking titles like Celeste, Griss and Shovel Knight. But two games that truly showcase the drastic differences that this genre offers come in Super Meat Boy and Ori And The Will Of The Wisps; games that have transformed the very idea of what a Mascot Platformer can be.

Every jump matters

Platformers live and die by their mechanics. You can have all the art assets in the world, all the thematic twists and turns of a daytime soap-opera but without tight mechanics, this all falls away. For all the differences Super Meat Boy and Ori have, this is the one thing they share – extremely tight, fun and engaging gameplay. Gameplay that feels great and gives you a fair challenge. “I think it’s [Super Meat Boy] a game with brilliant levels that complement top-notch controls presented with a weird theme. People like a fun challenge that feels fair and that’s exactly what Super Meat Boy is”, Tommy Refenes, co-creator of Super Meat Boy and upcoming Super Meat Boy Forever, told me with confidence about his game’s enduring appeal.

“I’m a strong believer in trusting my instincts on what feels right in a game. If I don’t like it, then it isn’t good. If I do like it, then there’s a good chance other people will like it too.” He continued. “Our goal was to never create something that felt shitty to play. For example, people often describe SMB as a “pixel-perfect platformer”, but the truth is there are no pixel-perfect jumps in Super Meat Boy. There are very difficult jumps, but there is nothing that requires timing and allows no room for error.”

That right there is a difficulty spike

Super Meat Boy is hard: there have been many instances playing through the game that I have wanted to yeet myself out of a window from frustration, but that has never been because failure felt “cheap”. An ideology that Tommy and Chris McEntee, the lead designer of Ori and The Will Of The Wisps, share in their approach to designing levels.

“I really pushed, as did the studio, for Ori and The Will Of The Wisps to be more accessible,” Chris told me when I asked him about his influence on the newest title. “In Ori and The Blind Forest, there is this infamous difficulty spike in the Ginzo Tree, and everyone would get stuck for a long time. It felt like the pacing was relatively smooth and then it hit that spike and a lot of people were like “I’m not prepared for this”. Chris’ time working on the rebooted Rayman with Ubisoft became pivotal in understanding how to approach difficulty curves in each section of Will Of The Wisps. “[When building] a level-based platformer, you’re thinking about a gimmick or a theme for each level, and you’re trying to expose it to the player in a nice safe way then put them in a situation where they are forced to use it to prove they know what it does, then at the end of the level throw everything you can at the player make them think “holy shit oh my God” and hopefully make it to the end where they feel that was a crazy ride and then do it all again in the next level”. Though Ori is a “Metroidvania”, each compartmentalised section flows in this way. It is this workflow of ideas and mechanics that keeps Ori and Super Meat Boy feeling both fair and fresh time and time again.

Timeless style, endless beauty

The art style of Super Meat Boy and Ori feels like a direct response to the sandy brown miserable landscapes that represented so much of the 00s. Super Meat Boy has a bold, colourful animation style that is massively representative of its origins as a Flash game on website Newgrounds. Newgrounds was, in fact, the place I first discovered the “weird” (as Tommy puts it) aesthetic that gives Super Meat Boy its enduring appeal. It’s a look so bold and so deliberate that it always looks fresh. This dedication to style is something Chris discovered whilst working on Rayman.

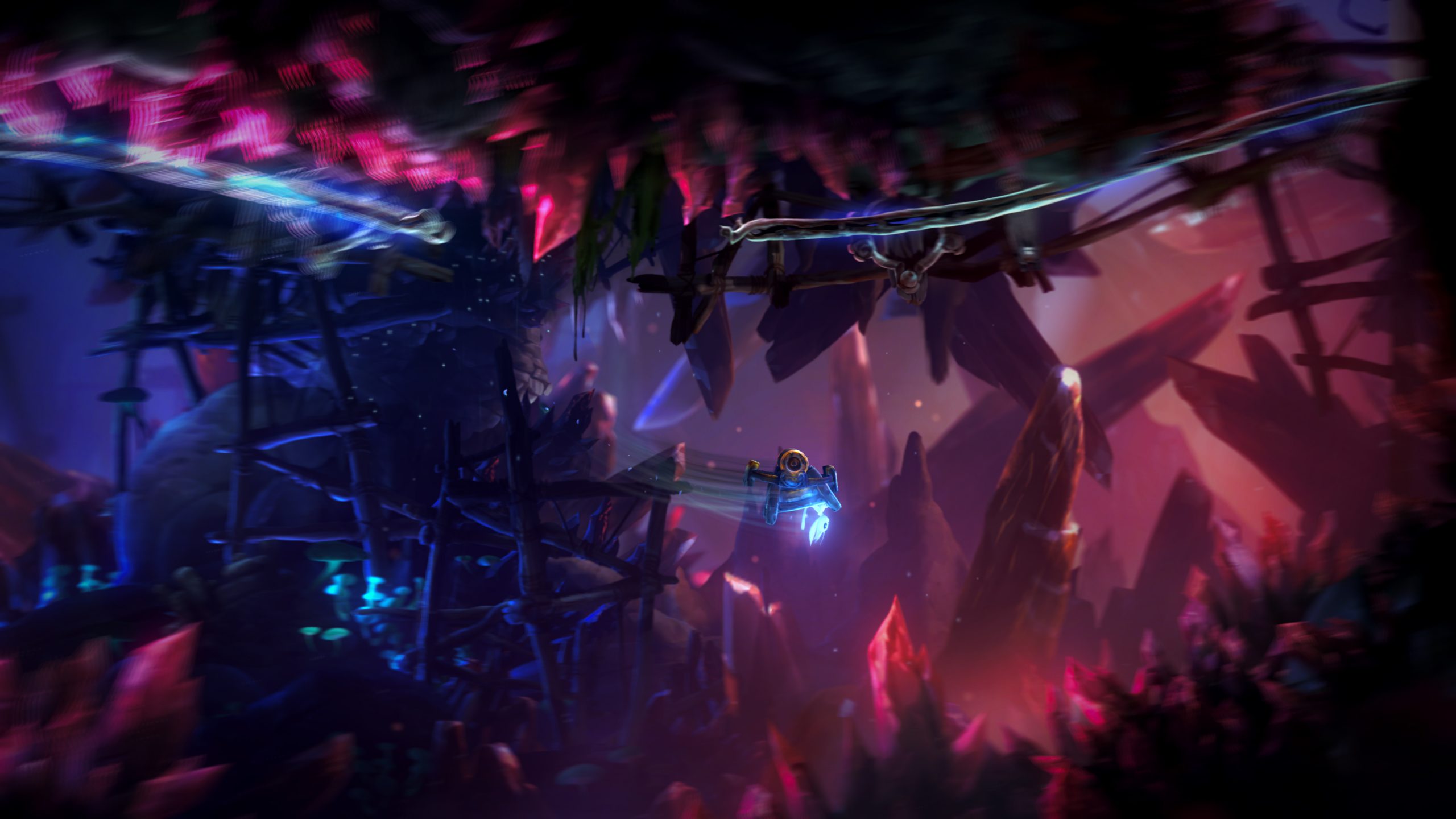

“Rayman had a unique Hanna-Barbera art style – that style of animation I hadn’t really seen in a 2D platformer at the time,” he said. “What I love about Rayman Origins, Rayman Legends and Ori is that the art style is pretty much timeless because of the way they were done and handled” he continued. “Compare Rayman to Uncharted 2 (released two years prior), it’s still great and beautiful, but it’s clearly dated when you look at similar games now you can see the difference, if you look at the two Raymans and Ori now, for the most part, it is visually quite timeless.”

This style and beauty doesn’t only serve to look gorgeous, however. Every aspect of the art design is deliberate in making sure that each level is as readable as possible for the player. Super Meat Boy isn’t a “pixel-perfect platformer” because Tommy and his team worked hard to make each level as readable as possible. Tommy told me that, when it comes to design, “[I am] a strong believer in trusting the people I work with… If I like it and if my designers like it then chances are it’s good.” It is that synergy that makes for both beautiful and practical world-building, as Chris clarified: “Readability is key, as long as the centre layer is as readable as possible, the artists can do what they want with the background they can make it super deep or very close, play with light and shadow as long as it is all in service of the centre layer. Making a game like Ori that is so artistically beautiful, it’s a constant collab between art and design.”

Stories that will fill your heart and rip it right out

Platformers, historically, have never been famed for their amazing storytelling. Most 90s mascots were jumping through levels with a base objective, but we never really dug deep into why we were doing it. Our beloved mascots were just big colourful avatars, memorable for their unique, fantastical looks and the way they played. The crowning achievement of indie platformers over the last ten years has been the way they have integrated a menagerie of thematic beats, from the zany and surreal to the grounded and heartbreaking. Though every platformer does feel different mechanically, it’s in the narrative that the true breadth of variety is shown.

Super Meat Boy, though a more traditional level-based platformer, uses cutscenes to tie together each of the 300 unique levels helping to maintain continuity and thematic flow through the whole game, making the adventures of Meat Boy, Bandage Girl and the villainous Dr Fetus feel like one continuing arc rather than a series of set-pieces. This also has the effect of making Meat Boy, an anthropomorphic cube of meat, somehow relatable on an emotional level.

“Nothing about SMB’s characters or story was an accident,” Tommy told me when I asked about the adoration for the characters and story of the game. “The story and how it was told from the cutscenes to the callbacks to older retro games was all on purpose.” That’s the key to the indie platforming sensation: the deliberate act of making a game that isn’t just tight and fun with some text running through it, but something that tells a deliberate story, whether that story is cartoonish and fun or, in the case of Ori, rip your heart out through your chest heartbreaking.

Compassion is key

“Ori is a very compassionate creature, even though he kills all these smaller mosquitos and monsters that inconvenience him, and we wanted to make sure that this compassion comes across clearly because it was pivotal to Ori’s arc,” Chris told me about continuing the story of Ori in Will Of The Wisps. Ori is a game hinged on deep and complex emotional and moral moments, told through little words. Other than points of narration at key moments, the team at Moon Studios wanted players to decide what to think and feel about the characters throughout the game. This is presented from the very beginning of the game, as Chris explained to me.

“In the prologue, we could have clarified that Kou, not only does she want to fly but doesn’t feel like she belongs because she sees a group of birds in the water that all look the same and she’s in this family of other creatures not like her – but we decided against ramming that [narration] in, and leave it, present it to the player and let the player decide what to feel, you don’t need to over-explain it – people understand”

Moon Studios are showing a huge level of respect to the audience, demonstrating that both the medium of video games and the genre of platforming has matured. Reducing narrative cues throughout the game lets players connect to characters that mean something to them, whether they are the protagonist or antagonist. Chris told me that “It has been so awesome to see people projecting themselves, their own feelings and experiences on what happens to these characters throughout the game”. An emotional connection to characters, their stories and their troubles regardless of how grounded or fantastical they may be are how stories survive, and characters become iconic.

The evolution of mascot platformers

We, as players, have truly been blessed by the ever-growing arsenal of new mascots that represent the growing maturity of our industry. There will, of course, always be a place for the likes of Mario and Sonic but now thanks to the ingenuity of studios like Moon and Team Meat, a fresh roster of heroes have become iconic. However, when I asked both Tommy and Chris about their characters as mascots, they had polarising views on the terminology.

“Meat Boy is a mascot, so I’d say yeah. SMBF (Super Meat Boy Forever) has several mascots, so there needs to be a new term for it, like a multi-mascot platformer or cinematic universe seed platformer.” Tommy told me with feverish excitement, promising an even fresher group of colourful and exciting characters for the Super Meat Boy universe. But where Tommy was enthused by the association, Chris was a bit more cautious about labelling Ori as a mascot.

“I have a deep attachment to mascot platformers, but I don’t know how well that term holds up in the modern age,” Chris told me. “Here’s your cartoon character hopping through a cartoon world. It doesn’t take itself too seriously, and it’s big and colourful for the kids, whereas you look at something like Ori, we’re telling this compelling story from start to end, weaving it all in and trying to keep the world very grounded and serious while also being colourful and whimsical. Mascot platformer isn’t the terminology that comes to my mind.” However, Chris does see the conversation surrounding indie platformers as mascots as a sign of the platformer’s place artistically. “It is a sign that there is a new age of platforming that has come. I think they’re all maturing as a genre and people are exploring it in many different ways. Like Celeste, maybe at first you look at the art style and think it’s a cartoony fun game that doesn’t take itself too seriously, but if you look at the themes that are in the story, you see that it takes itself very seriously and it’s trying to tell some pretty deep stuff.”

Regardless of the label attached to these projects, characters like Ori and Meat Boy have become the faces of a genre characterised as much for their artistic beauty and narrative brilliance as their mechanics. The mascot platformer has come of age and has become the flag bearer for new, innovative and exciting experiences as legitimate as any AAA blockbuster.