Indies Are Looking To Gaming’s Past To Build A Retro Future

History has plenty to teach us about game design.

Indie games are a bastion. A bastion of creativity, a level slate, a separation from the machinations of the wider industry. Most importantly, they’re a breathing space, a salve against the irritability of bigger-budget games.

Increasingly, though, the genre is being recognised alongside its grander cousins. The enormously successful Cultist Simulator, for example, rubbed shoulders with God of War and Assassin’s Creed at this year’s BAFTAs. Ukie’s chairman, Jo Twist, praised how indie games “drive much of the innovation and creativity that underpins the wider sector,” strong words from the head of the only trade body for the UK game industry.

“Innovation” is a word thrown around the wider narratives of indie development so blankly and so often, it verges on a kind of friendly word salad. The medium’s innovations are never elucidated upon and are often orientated solely to the future; indie games are not catalysts of modernity.

By consistently seeing indie games as building blocks for the industry going forward, well-meaning praise ends up forgetting the role indies play in re-evaluating gaming’s past. Indie titles aren’t only to be understood as a path to a future; they’re successful methods of modernising antiquated systems and design choices that have been left behind by the mainstream industry and, by extension, dragging them back from the brink of the history books.

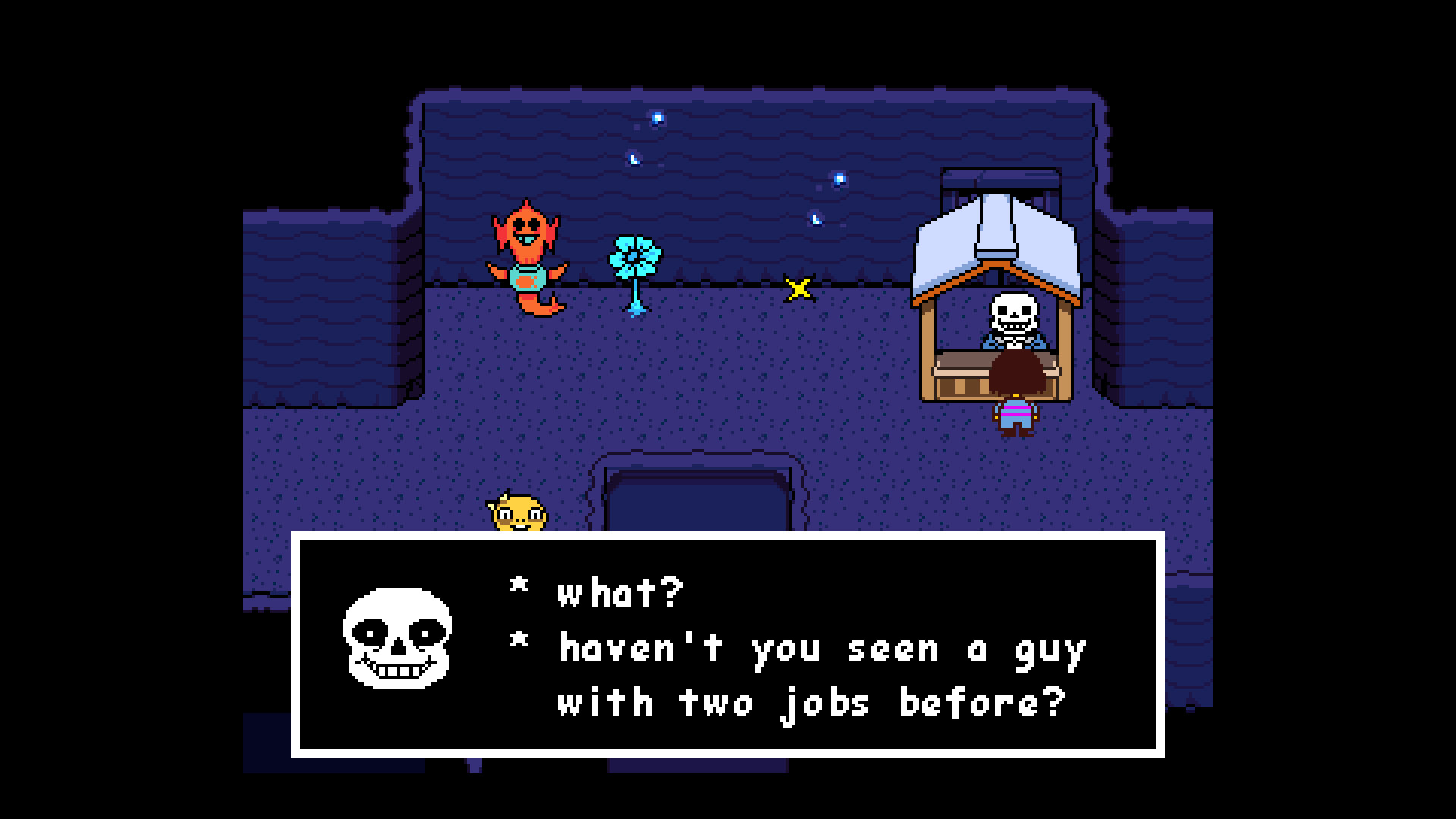

Perhaps the most celebrated indie game ever made, Undertale was praised to the moon and back for its usurpation of player expectation, excellent writing, sense of scale, fourth-wall breaking story, and its nostalgia-inducing design. The game was well-recognised for its Earthbound influences, with Undertale’s sole creator, Toby Fox, cutting his game development teeth with Earthbound ROM hacks.

While the Earthbound influence was noted, it was quickly left at the door as a context filler before Undertale was, perhaps rightfully, lauded as one of the best things to happen to indie RPGs for a long time. Very little was written, though, about how Fox managed to revive a style of RPG that seemed so lost to time.

Earthbound was by no means an unknown entity; the game has been permanently lodged in the recesses of JRPG discussion since its release, helped along of course by its difficulty to obtain. Earthbound was, though, a game seen as wholly original, echoed in reviews even as late as 2013, where IGN concluded the game was one of the “most unique RPGs to date”. Why, then, did Earthbound’s influence go unused for so long?

Just two years after IGN’s review was written, a one-man development team managed to recapture the same lightning-in-a-bottle magic as its influence by deciding to look backwards. By touching ground that the modern gaming scene regarded as sacred, an indie gem was born.

More importantly, a neglected sub-genre of obtrusive JRPG games was thrust back into the limelight, not for nostalgia, but for re-appraisal of what developers and the industry had missed. Undertale is an example of indie gaming’s knack for combining systems, stories, and aesthetics believed to be dated and breathing new life into them.

2012’s Lone Survivor ran with a similar philosophy, touching on the hallowed ground of survival horror greats before it. The game’s central inspiration, Silent Hill, has been lauded, much like Earthbound, as unrepeatable. While the game differed from its inspirations substantially in gameplay, by successfully adapting Silent Hill’s penchant for inward-looking horror to two-dimensional aesthetics it earned plaudits. Instead of solely trying to focus solely on the future, Lone Survivor achieved its deserved success by dusting off the not-so-distant past.

An argument can be made, though, that cases like Earthbound and Lone Survivor do not necessarily count as examples of indie’s successful revisionism as their appropriation of the past merely lies in aesthetics, tone, and narrative. Many indie games, though, successfully incorporate older mechanical and level design choices without them looking out of place or gimmicky in gaming’s modern milieu.

Some games exist on the merits of adapting older mechanics unwaveringly, resulting in titles that usurp modern pretences merely by reminding us of our foundations. Minit, for example, was a breath of fresh air when it released last year, but, at its core, was based on mechanics found in 1986’s The Legend of Zelda, a blank canvas of exploration, challenges, and intrigue.

By applying a time constraint and a unique approach to death with this twenty-year-old canvas, Minit was able to instil modern palettes with the same type of pure, gameplay-focused joy Link’s first players must have had. This was not solely achieved by forward-thinking innovation, but by analysing the past to see what could, in the blankest of terms, be recycled.

Retro-inspired FPS games have seen something of a renaissance period in the indie scene, with titles like DUSK appealing to those who reject the modern, slow interpretation of the genre. The arcade-like, pacey nature of nineties-era first-person games has been lost as we entered the early 2010s, with the genre seeming, well, played out. That view, though, couldn’t be further from the truth and has facilitated a rise in these classic FPS games.

“Indie games are great for a lot of reasons,” says Jason Mojica, one-half of the development team behind Prodeus, a retro-inspired first-person shooter. “They aren’t beholden to the masses, they can be whatever they want, no excuses, they don’t answer to anyone.” Mojica’s belief in indie games being distant from the workings of the zeitgeist’s taste led to Prodeus’s philosophy to “hearken back to the old days,” resulting in a game that doesn’t so much incorporate older design choices but celebrates them wildly. This game’s development isn’t simply a nostalgia trip, it’s a way to bring forgotten genres into the present.

“We definitely take a high degree of inspiration from the older games. A lot of our layouts use non-standard flows which allows them to go off the rails a bit and find their own direction. This whole level design process has been a joy to work with, it’s something we’d recommend all level designers going through at least once in their careers,” Mojica says.

The suggestion to bring in facets of the past speaks volumes. In film, directors aren’t afraid to reference back; in literature, writers aren’t afraid to learn from dusty tomes; but in games, developers are afraid to dip into the past. By committing to a machine that runs on some lofty modernisation theory – that is, to always be pushing “forward” and consume – mainstream gaming is refusing to face its own past and appreciate the innovations that it forgot.

Experimental, esoteric titles can play around with the past, too. Colorfiction, the mind behind psychedelic, genre-bending titles such as 0N0W and the upcoming Ode To A Moon, is one such example. Colorfiction, real name Max Arocena, looks to the past, despite his work being lauded as future orientated:

“I think that a big part of advancing any medium is looking at the past for inspiration and insight. I was lucky to grow up through the various stages of game development, from Duck Hunt to Crysis, so I think this has really impacted the way I personally look at games and as a result my own contributions to the field.”

While Arocena looks to isometric RPGs and classical SNES titles for reference, his real love, much like Prodeus, lies with 3D games of the nineties and noughties. For Arocena, “there’s something about the animations, mechanics and atmospheres that are weirdly timeless,” as though the depths of that era are yet to be explored.

Stalker, too, is a massive reference point for Colorfiction’s games. “Stalker, that game changed everything. It’s curious because it wasn’t necessarily open world but felt more alive and free form than all the Bethesda’s titles that I had played until that point. It’s got the perfect atmosphere, soundscapes, design, gameplay, just everything is fantastic, to a degree that makes you overlook the many technical bugs that are present.”

Why, then, is it so difficult for today’s games to inspire the same sense of awe and wonder in their audiences as the cartridges of yore? Arocena has a theory, mostly due to the expectations we have of modern games, as opposed to breadth we offer to older, classic games:

“Nowadays the conventions and expectations have stacked to a point where it’s becoming very difficult to break free from the mould without serious audience backlash. From localization to multiple OS or hardware support etc., these are features that take as much development time as creating the game itself, time and resources that could be invested on making the actual game better.”

Of course, older games were, in some cases, hampered by technological limitations which do not exist in modern times. If these games, systems, and ideas were held back by the technology they had in their arsenal, then surely it is worth revisiting them now that the technology is available. Arocena runs with a similar theory, which he attributes to the success of games like Dusk:

“There used to be a memory limit as to how gigantic a game level could be and the variety of animations, sounds, and AIs you could place, but now that boundary is exponentially larger. So why not go back to a formula that worked and expand on it?

You have games like Dusk and Amid Evil that perfectly encapsulate the feeling of fast-paced FPS games of the late 90s and yet advance them further. Not because they implemented photo-realistic graphics or gimmicky game mechanics, but because they studied a system that works and just made it better.”

When games like Prodeus add a level editor or incorporate “old” systems, it isn’t to idly revel in nostalgia. As Arocena elucidates, sometimes the systems are there to be made better, not to be deserted once they pass their sell-by date. Mojica, too, expanded on this idea, tying up the whole debate eloquently:

“Every once in a while you’ll get something that really stands out and can’t be ignored by the larger studios. […] It’s just one of those things that takes time and a lot of voices championing for their favourite content. Once people see value in your ideas and what you’re doing, the next step is usually emulation.”

Indie developers, thankfully, know that the past has value, and aren’t afraid to show the rest of us what we missed.