198X Review (Part 1)

An attractive but entirely hollow 1980s nostalgia machine.

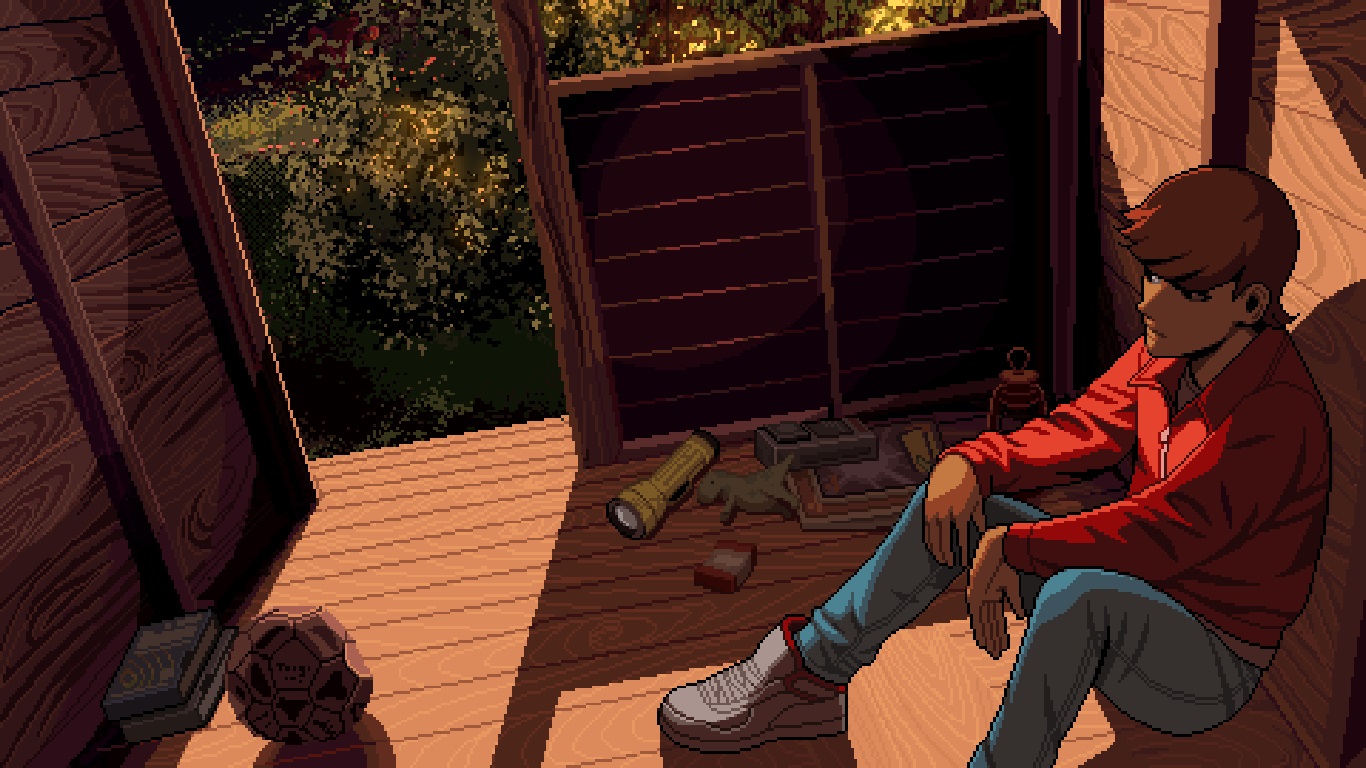

I didn’t grow up experiencing video games in arcades so I don’t come to 198X’s ‘arcade epic’ with any particular fondness for that supposed golden age of gaming history. I don’t relate to its story of Kid, a teenager stuck in suburbia just outside the city, self-actualizing through the experience of discovering an arcade and mastering its game cabinets through hours and hours of play in the year 198X.

This first part of the game—the full game is set to be released in more installments—takes place over five different minigames, pseudo-arcade cabinets, interspersed with narration from Kid. In order, those games are: “Beating Heart,” a beat ’em up in the style of Streets of Rage; “Out of the Void,” a side-scrolling shoot ’em up in the vein of Gradius; “The Runaway,” a racing game similar to Turbo; “Shadowplay,” a ninja side-scrolling platformer like Ninja Gaiden; and “Kill Screen,” a procedurally generated dungeon crawler.

Even if I were of the 1980s cohort that 198X targets, its story would likely still fail to affect me because it’s so generic. Its unnamed protagonist (only given the name “Kid” in promotional materials) says quite a lot but none of it has impact or means anything, because there’s no specificity. 198X’s generic nature, its unnamed protagonist and setting, seems inspired by gaming’s long history of nonspecific storytelling meant to facilitate player externalization.

In 198X, and I’d argue in most other cases as well, the approach falls flat, because specificity is what creates dimension and character. 198X’s blank slate Kid monologuing about how the world doesn’t understand them and growing up is hard never lands. The only effective aspect of Kid’s narration is the voice performer, Maya Tuttle. The decision to have the character’s voice be feminine while the character presents as boyish provides a much-needed element of nuance, and Tuttle’s performance itself is imbued with a sweet melancholy.

From a narrative perspective, this first chapter has another problem: as the game itself says at the end of this first part, “the story has only just begun.” This lack of closure leaves the game’s narrative feeling even less dynamic and satisfying, because the presumably interesting aspect of the tale, a hint that the games at the arcade will merge with the Kid’s reality, only just begins as of the end of this first installment.

While 198X’s narrative does have promise, its mechanics do not. Ultimately, the majority of 198X’s experience is playing poorly optimized, frustratingly repetitive minigames. These minigames are much less interesting versions of what they could be, and the side-scrollers are particularly egregious for their punishing nature that necessitates trial-and-error memorization to complete. The ninja game is the worst offender, with way too many instant-kill traps.

I think 198X hopes that its minigames operate as trials of mastery, that they instill a sense of accomplishment upon completion that mirrors the sense of autonomy that Kid ostensibly feels when they play them. However, other games have used similar mechanics of challenge as a metaphor for their narratives to much greater effect; namely, last year’s Celeste which uses these mechanics to reflect a battle with mental illness. But 198X has no such lofty or interesting narrative intentions for its mechanics to emphasize. As it stands, 198X’s gameplay has little interaction with its narrative, and that’s a shame.

Ultimately, I leave 198X wondering who it is for and why it exists. Clearly, it aims to appeal to those punk arcade dwellers of the 80s that its protagonist desperately fawns over, but I don’t expect 198X’s narrative or gameplay will deliver to that demographic. Narratively, those players would be better served by a story with a more focused and individualized approach, perhaps leaning into the gender dynamics already at play with Kid and making them an outsider because of their gender expression rather than some vague sense of dissatisfaction; then the game might speak to gaymers who grew up in the 80s. For those arcade players that love the style of the retro games that 198X imitates, there are more polished, more interesting titles available in each of the genres that 198X includes.

198X is aesthetically pleasing. Its bright, accomplished pixel-art and synth-fueled music capture its desired tone perfectly. But if that’s all that 198X is, I’m not sure it’s worth anyone’s time. Even if you are interested in a pretty but empty 80s nostalgia drip, I’d suggest looking elsewhere; there are plenty of options.

[Reviewed on PC]